Nonverbal Communication

Definitions

| Verbal Communication | – spoken or written words |

| Nonverbal Communication | – vocal sounds (groans, laughter, hums) – vocal quality/tone (warm, soft, hard, cold, hard, harsh, quiet, loud, hesitant, confident) – silence, hesitations, voice catches – facial expressions (macro and micro) – eye contact (looking away, looking down, focusing on hands/feet, wide eyes, nervous blinking) – body positions, movements, hand and arm gestures – gasps, sighs, and slowed, rapid, or ragged breathing – sweating, face/neck/chest flushing – behaviour (crying, slamming doors, disengaging, moving away, picking at clothes, covering mouth, changing topic, etc.) |

Being aware of the role of nonverbal communication is critical whether we are sending or receiving a message, that is to say, speaking or listening. Nonverbal communication:

- serves several purposes, such as emphasizing, commanding, illustrating, displaying emotions, and demonstrating intention

- is often habitual, performed unconsciously, and therefore may be something of which an individual is unaware

- differs from culture to culture and person to person

- reveals true feelings despite words being used

The realm of nonverbal communication is a rich form of human communication. Ivey, Ivey, and Zalaquett note that nonverbal communication is the first indicator of what another person is thinking and feeling (it is also one of the reasons people struggle to accurately interpret text messages and emails). Nonverbal cues may be the only hints as to what is really happening. For example, a fleeting facial expression, such as a nose wrinkle or curled lip, can signal disgust, even when the words do not convey this feeling. Observing the other party can be a window into what they are really trying to say, as well as what they are trying to avoid saying.

| Consider… | ||||

| “Your presentation was interesting.” | + | lively voice tone, relaxed open and forward body posture, direct eye contact, mouth curved up in a smile, palms up | = | “Your presentation was interesting (and I liked it).” |

| Versus | ||||

| “Your presentation was [pause] interesting.” | + | dull voice tone, arms crossed, back-leaning and stiff body posture, chin raised, mouth tight with one corner raised (i.e. in a sneer), one eye more closed than the other corresponding to raised lip (i.e. side eye), head tilts to side on “interesting” | = | “Your presentation was interesting, but I feel contempt/am jealous/did not agree.” Or “Your presentation was not at all interesting.” |

Observations attached to nonverbal communications cut both ways, remind Ivey, Ivey, and Zalaquett. You can use observed nonverbal cues as the first indicator of emotions and congruence between what is said and what is meant by the other party, and so too can they read your nonverbals. Being a thoughtful observer, of your own nonverbal cues as well as those of the other party, allows you to become more aware of the different layers of a conversation and identify incongruencies – between you and the other person, or between what is and is not said.

Caution must be exercised in interpreting nonverbal communication as it is often culturally dependent. Culture is not homogenous, so there are very few hard and fast rules to reading nonverbals. Different levels of cultural emotional control/expression are formed through family upbringing, acculturation, personal comfort level, social significance of emotional expression, and purpose for expressing emotions.

It is important to note that the nonverbals of an individual from a culture other than your own may be disquieting because of the intensity or lack of intensity. One party may be viewed as inscrutable, emotionless, or deceptive, when simply it is culturally inappropriate to express or divulge emotions in public or to a stranger. From the other side of the conversation someone expressing themselves nonverbally (such as with big gestures, lively voice tones, or animated face) may be seen as untrustworthy, erratic, unstable, frightening, and/or immature. Both parties in the conversation may believe that their nonverbal expression is appropriate.

As a skilled party to a conflict conversation, consider your own nonverbals and potential cultural dimensions. It may be appropriate to subtly mirror the other party. Mirroring – synchronous or complementary body language – occurs naturally when parties are attuned to one another and communication is effective. People who are not communicating effectively may exhibit movement dyssynchronicity (e.g. jerky body movements and shifts, turning away). Ivey, Ivey, and Zalaquett suggest that intentional mirroring can help stimulate mirror neurons that are naturally activated when people experience empathy.

The Communication Gap

Communication is thought to be effective when the intent of the message being sent is consistent with what is being understood and responded to by the receiver. If this does not happen because of external or internal filters such as those discussed throughout this course, a communication gap occurs.

A misunderstanding or communication gap may also occur when one’s words and actions do not convey the same message: when what someone is saying and how they are delivering the message do not match. This incongruence may lead to confusion or disbelief on the part of the receiver who may then not know how to respond appropriately, and the sender may not attain the desired outcome.

When verbal and nonverbal messages do not agree, the receiver usually believes the nonverbal cues even though he or she is not consciously aware of doing so.

| For example, if someone says…… |

| “I really want to hear about your experience.” |

| …and, at the same time, is chatting with someone else as he or she rushes out to lunch, what you will hear is….. |

| “I want you to think I’m interested in your experience, but right now I’m actually more interested in what this other person has to say and in getting something to eat.” |

We now know that we rely on nonverbal communication to provide supportive and concordant meaning to a message. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the characteristics and impact of what is happening in terms of the body language and intonation that accompany verbal messages.

Listening

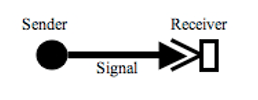

In its simplest form, communication occurs when a message is sent by one individual and received by another. It can occur in person, on the phone, in an email, through a hand-written sticky note, in a snail mail letter, or though body language. It looks like the diagram below.

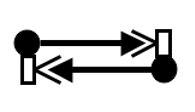

Communication is also a two-way process that is completed by a response or reaction by the receiver upon receipt of the message, as shown in this diagram that depicts the encoding of a message (by the sender), the decoding of a message, (by the receiver) and nothing else.

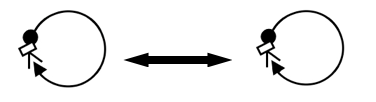

However, we know that sending and receiving messages does not happen in a void. They both occur within a context, like this:

Communication is not suited to a distillation of common rules where there is a simple transfer of information and should be instead understood as a process that undergoes evaluation before, during, and after the conversation. When viewed this way it is possible for participants to work together with the goal of understanding each other as openly as possible.

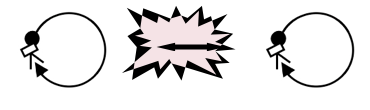

While travelling from the sender to the receiver, a message may encounter interference along the way. External factors such as noise or other distractions may interrupt or alter the message being sent. These are known as filters.

Communication consists of multiple layers; it’s a package of several messages. If we focus on only one part of a communication or one part of the packaged message, we will certainly miss much of what is going on. A message often tells us basic information, something about the sender of the message, what the relationship between the sender and the receiver is, and what the person sending the message wants done. It is rare that a message does not somehow include one of these parts, and can include multiple combinations of these parts although what a sender is disclosing about themselves or their perceived relationship with you may not be done consciously.

To make sure we are communicating effectively, it is important to listen to all the meanings in messages, not just for the main content.

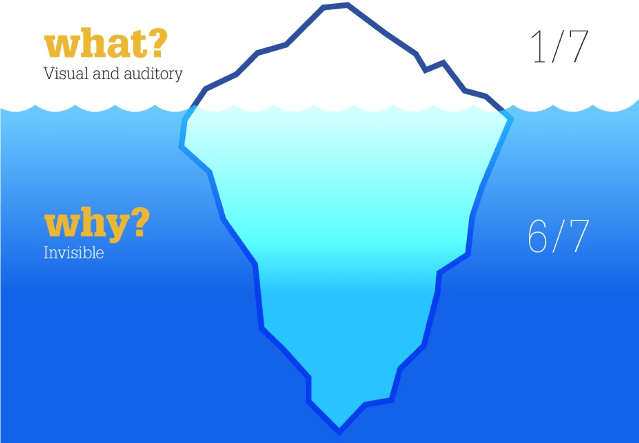

Theory: Iceberg Model

Originating with Sigmund Freud, The Iceberg Model is now used in training and analysis of communication. Above the water’s surface, the iceberg represents all of the observable acts of communicating, like what is said and body language. Below the water’s surface, however, are all the motives, emotions, experiences, needs, and norms that make up the people communicating. Though they are invisible to the outer conversation, they are what influences most of the conversation. The information hidden under the water contains 6/7 of the relevant information in conflict communication.

With the help of skillful questioning and active listening skills, you are more likely to understand what is happening beneath the water’s surface, and therefore have more successful, meaningful communication experiences.

Theory: Five Levels of Listening

According to Don Crawley, an author of multiple books on the customer service and sales industry, we have five distinct levels of listening we use, depending on the given situation. They are: Ignoring, Pretend Listening, Selective Listening, Attentive Listening, and Empathic Listening.

Ignoring

While this often is blatantly clear, as it is not listening at all to another person, it is also important to note that people can get the impression that you are ignoring them if you are multi-tasking and your attention is not fully focused on the matter at hand.

Pretend Listening

Your full attention is not on the conversation, and it’s clear you are distracted. You might be on the phone, making affirming statements like “mmmhmmmm” or “ I see” while you work on other tasks, or you might be in a face to face conversation with another person who has a faraway look in their eyes.

Selective Listening

Selective listening starts with us paying attention, but devolves into only listening when the conversation is about something we are particularly interested in, or is something we agree with, otherwise we slide down into pretend listening or ignoring as the conversation takes other turns.

Attentive Listening

Attentive listening is a form of careful listening, but our entire mind is not devoted to the task. Instead, we are thinking of how we might respond, counter, or argue with what is being said. We are also determining whether they are right or wrong on the spot instead of waiting for them to finish what they are saying.

At this point, it should be clear that the first four levels of listening do not devote full attention to the speaker, failing to give them the respect they deserve. In order to actively listen, we must move on to empathic listening.

Empathic Listening

Empathic listening, also known as active listening, is when we listen carefully and respectfully, engaging fully in putting ourselves in the place of the speaker to better garner understanding. In Crawley’s example, he talks about IT support people listening to every caller as if it is the first time that they have heard this problem before.

To achieve empathic listening, we must: slow down, be patient, talk less and listen more, repeat back what has been said to us, ask clarifying questions, and be specific about the needs and wants of the speaker. Crawley encourages asking yourself where your focus is as you engage in listening, noting that if your focus is on yourself you are engaged in one of the first four levels of listening, and that only when the focus is on the speaker are you truly engaged in empathic listening.

It is also important to note that unlike sympathetic listening, empathic listening does not mean that you agree with the other person, just that you are trying to understand the situation from their perspective.

Additional Complications

An additional complication occurs because our messages can be explicit or implicit and congruent or incongruent.

| Explicit | Explicit messages are clear and obvious to the average listener. There are no doubts about what is intended by the content. “I know how to do this task.” |

| Implicit | Implicit messages can be explosive. The speaker could say he or she didn’t mean to imply what you inferred. The speaker can say, “I didn’t say THAT!” and the listener could reply, “Yeah, but you meant it!” “I’ve worked here for 15 years.” |

| Congruent | Accompanied by a sad or worried expression: “I am unhappy about the project budget.” |

| Incongruent | Accompanied by a furrowed brow and loud voice. This incongruence is noticeable and confusing. Does it mean the speaker doesn’t want to talk about what is causing the anger or wants to be left alone or wants help but doesn’t want to have to say so. “I am NOT angry.” |

Messages with a dichotomous or incongruent nature can cause serious problems, especially for children and people in a subservient or precarious position (real or perceived).

Listening to Understand

Before the creation of the International Listening Association and the establishment of listening as a field of study, Dr. Ralph Nichols fostered the original study and development of listening. He claimed that the effectiveness of communication hinges “not so much on how people talk but mostly on how they listen.” Education has long assumed that when children are taught how to speak, read, and write, they are also learning how to listen. In the years following Dr. Nichols’ original work, we have learned that nothing could be further from the truth. Listening is an active skill in its own right and, like all other active skills, must be refined, practiced, fine-tuned, and practiced some more.

Extensive testing conducted at the University of Minnesota, Florida State University, and Michigan State University led to the understanding that within minutes of listening to a short lecture, most people will remember only 50% of what they heard. After eight hours, the average person is lucky to remember 25% of what he or she heard.

Clearly, listening involves much more than the physiological process of hearing and is an integral part of our daily lives. Being able to listen effectively has a significant impact on our interaction with others at home, in the workplace, and in the community.

Barriers to Communication

Barriers that contribute to miscommunication may be divided into three main categories: external, internal, and language and behaviour. These barriers can affect both the sender and the receiver of a message.

Definition

| Communication Barrier | anything that interferes with or reduces the ability of a sender and receiver to understand each other. |

External Factors

As previously noted, barriers to effective communication might be the result of an external environment that is not conducive to interpersonal conversation as a result of noise, interruptions, physical inability, or physical discomfort.

Internal Factors

Internal barriers might exist because of a person’s values, background, experience, assumptions, and expectations: what has happened in the past, what is thought to be likely to happen this time, and what is the desired outcome.

Language and Behaviour

Other barriers are a consequence of an individual’s use of language and the resulting behaviour.

Consider the following in terms of language:

- People don’t always say what they really mean, perhaps because of fear or confusion.

- People are not always aware of their real feelings to be able to correctly identify them.

- Feelings are sometimes hard to put into words.

- The same words have different meanings for different people.

- Cultural differences and technical jargon may lead to misunderstanding or lack of understanding.

The response by the receiver of a message may be affected by the following:

- People sometimes hear only what they want to hear.

- People might tune out because they believe that they already know or don’t wish to hear what the person is going to say.

- People may dismiss comments as being irrelevant to the situation.

- People are often preoccupied with what they are going to say next so that they don’t listen carefully.

- There is no accurate feedback or confirmation of understanding.

- There is a lack of empathy and understanding.

Putting Up Barriers

Psychologist Carl Rogers notes that when interacting with others, in particular when feeling threatened, individuals often use communication barriers to protect or defend themselves by taking an approach such as the ones listed below.

| criticizing | judging or evaluating the other person negatively |

| name-calling | making demeaning or stereotypical comments |

| diagnosing | analyzing |

| evaluative praising | making a positive judgement of the other person with the intent to manipulate |

| ordering | commanding the other to do something |

| threatening | trying to control the other’s actions by warning of dire consequences |

| moralizing | telling others what they “should” do, think or feel |

| interrogating | questioning excessively with leading, closed-ended questions |

| advising | giving the other person a solution |

| diverting | switching from the other person’s concerns to your own topic |

| logistically arguing | attempting to convince with facts or logic |

| reassuring | trying to stop the other person from feeling negative emotions |

Impact of Communication Barriers

Attempting to deal with communication barriers may have an adverse effect on an individual and interfere with his or her ability to respond appropriately. On a personal level, the person may experience . . .

- diminished self-esteem.

- defensiveness, resistance, resentment.

- dependency.

- withdrawal.

- feelings of defeat or inadequacy.

- inability to constructively express feelings.

- difficulty with problem-solving.

Elements of Good Listening

Improving the ability to listen, as defined earlier, can be managed by following this advice:

- Give full attention to the speaker: be open-eared and open-minded.

- Put other thoughts temporarily aside in order to focus on what is being said.

- Resist distractions by periodically summarizing in your head what has been said.

- Listen to more than just the words: tune in to the feelings behind them.

- Observe and give nonverbal signals that indicate attention and interest.

- Accept that the message is important even if it arrives in a form that you don’t like or comes from someone you don’t like.

- Listen to all the other person has to say rather than tuning-out half way to plan a response.

- Suspend judgement about what is being said, at least until comprehension is complete.

- Avoid a personal interpretation and listen to what the speaker is really saying.

- Verify that the message has been received in the way that the sender intended.

Active Listening Skills

To be most effective as a listener and thereby gain understanding of another person’s perspective, one must be an active participant in the listening process.

Active listening involves being ever-present in the situation, paying attention to both the nonverbal and verbal aspects of communication, providing an environment that encourages meaningful discussion, and using reflecting skills to clarify understanding. The increased understanding that results from active listening is a critical component of collaborative dispute resolution.

As an active listener, we must be continuously aware of the information being conveyed both to the speaker and by the speaker through nonverbal communication.

Attending

As an active listener, it is important to let the speaker know you are paying attention and interested in what is being said. This information is conveyed through your body language and your behaviour within the physical setting:

Posture

- facing the speaker squarely or at an angle

- inclining one’s body toward the speaker

- maintaining an open posture

- positioning yourself at an appropriate distance, respecting personal space

Body Motion

- moving slightly

- avoid fidgeting

- mirroring

Eye Contact

- looking at the speaker to indicate interest and a genuine desire to listen

- shifting gaze away occasionally so as to not be perceived as staring

- being aware of cultural differences which may limit or alter type of eye contact

Environment

- giving the speaker your undivided attention

- avoiding distractions (phones, visitors)

- eliminating physical barriers when possible

Encouraging

Encouraging skills are those that invite the other person to engage in a dialogue. They are often verbal, though minimal, and let the speaker know that you are prepared to listen to his or her comments.

| For instance … | |

| offer a non-coercive invitation to talk such as … | “I’m interested in hearing your perspective on this matter.” “I’d like to hear more.” |

| describe body language. | “You look angry and your arms are crossed. What’s happening?” |

| remain silent, waiting for the other person to begin. | “……………” |

| make brief comments to encourage the person to continue speaking, like … | “mmm”, “tell me more”, “yes”, “really”, “and?”, “go on”, “then what?” |

| ask mostly open questions to encourage the other person to expand or explore. | “What was the significance of that particular brand of car?” “What makes that particular Cadillac important to you?” |

Also…

- allow the other person an opportunity to think about what he or she wishes to say

- ensure your questions are designed to help the speaker discuss his or her own concerns rather than simply provide information for the listener

- remain attentive, observe the other person, and think about what has been said

Facilitating

Facilitating skills refer to the attitude or approach the listener brings to a situation that encourages others to share their thoughts and feelings.

Warmth

- conveying a degree of caring for others

- communicating nonverbally through gestures, posture, tone of voice, touch, or facial expressions

- perhaps expressing verbally “If this is important to you, it’s important to me. Let’s talk about it some more.”

Genuineness

- being honest and open about one’s thoughts, feelings, and interests (concerns, hopes, expectations assumptions, priorities, beliefs, fears, values, and needs)

- being self-aware, accepting, and able to express oneself appropriately and responsibly

Respect

- observing to learn about the uniqueness and capabilities of others

- accepting their ideas, feelings, experiences, and rights

- believing in the other individual’s ability to solve their own problems

- valuing the potential of a person

Respectful Facilitation

The following five simple tips will help you facilitate with respect:

- Be non-evaluative. Encourage full expression by the other person without showing an opinion of what is being said.

- Respond in a modulated tone of voice until a basis is built for warm expressions.

- Give undivided attention to whoever is speaking and demonstrate commitment to understanding the person.

- Show you are trustworthy by being genuine and spontaneous.

- Maintain eye contact without staring.

Questioning: Open/Closed

Questioning may be used: to encourageCl conversation, gather or expand information, eliminate confusion, and clarify or deepen understanding. There are two types of questions, closed-ended and open-ended, each of which is appropriate in certain circumstances.

Closed-ended Questions

Close-ended questions limit responses to “yes,” “no,” or “’maybe”; they most often begin with words such as “can”, “do”, “was”, and “are”. While closed questions can be used to clarify a point when no further information is required or desired, they are restrictive and provide little information.

Closed questions are often leading or entrapping, taking the discussion in a particular direction determined by the questioner, as opposed to allowing the responder to explore their thoughts and feelings.

| For instance: | “Are you clear about the directive I gave you?” “Did you hear me?” “Can you give me that report?” “Don’t you agree that we have a problem?” “Were you here when it happened?” “Do you want to discuss it?” |

Closed-ended questions are most useful in situations where very specific information is required, when simple clarification is needed, or where there can be no discussion or debate such as in emergencies.

Open-ended Questions

Open-ended questions cannot be answered with “yes,” “no,” or “’maybe”; they begin with words such as “how’, “what”, “where”, “when”, “why”. Open questions can be used to gather information because they are broad in nature and tend to reduce defensiveness by being non-judgmental or not blaming.

Therefore, open questions encourage the speaker to elaborate and to provide more information based on his or her own needs. Open questions are an also effective means of getting all the information needed for understanding.

| For instance: | “What is it about this policy that’s a problem for you?” “When you say ‘it’s obvious’, what you mean by that?” “What concerns you about the new plan?” “If it was up to you, how would you handle this?” “Why are you thinking this will be challenging?” “When did you first begin to think the plan wasn’t going to work?” “Where do you think would be the best place to begin?” |

Open-ended questions may be used to elicit new or expand existing information, or to probe deeper to uncover concerns and interests.

Clarifying Questions

What’s really going on? Consider this example:

An employee may request a raise in pay (their position) when they are feeling undervalued by the employer. Through an exploration of the need to be valued for their contribution to the organization (their interest), it may become evident that a larger office, a different title, or even verbal recognition would meet the need for recognition, contribution, and advancement more fully than an increase in salary.

It could even be that the employer was unaware the employee felt undervalued and actually thinks very highly of this employee. With this awareness, a number of changes might occur to address the need.

With clarification, opportunity to understand and find a better resolution is expanded.

| For instance: | “When you say . . . what do you mean?” “How can that cause difficulty for the staff?” “What led you to make that assumption?” |

To help the other person clarify the interests beneath their position, the skilled party can use a number of interventions. Use clarifying questions to:

- Explore judgment words

- “good”, “bad”, “effective”, “appropriate”, “disappointing”

- Ask about what is important or significant to the other party about the issue

- Point out/highlight patterns of behaviour to explore underlying reasons – of which the other may not even be aware.

- Avoid: “you always/never”; try: “I notice …/I see…/etc.”

- Determine whether a problem is a screen for more general problems/differentiate between symptoms and problems

- For example, is the conflict between coworkers really about the parking space or about recognition and fairness in the workplace?

Probing Questions

A probe is usually an open-ended question or request for more information that follows a statement made by another person, often in response to an earlier question or paraphrase you have voiced.

| To be relevant and continue the progression, a probe is typically hinged on a word or phrase mentioned in the person’s statement. |

A probe is intended to encourage the speaker to reflect on the statement just made and to expand, clarify, re-examine, or explain further. As mentioned previously, probing is an effective tool for uncovering a deeper level of motivating interests than what has appeared initially in earlier discussion.

Probing helps assure that both of you are as clear as possible about what information is being disclosed and what the speaker intended to convey in his or her statement. Following are some examples of probing questions and requests for more information:

To expand

- What more can you tell me about that?

- Tell me more about . . . . .

- What else about . . . . . would you like me to know?

- What more you would care to say about . . . . .?

- Say more about . . . . ..

To clarify

- What might be an example of that?

- What does “safe” mean to you?

- Please tell me what safe means to you.

- In what way?

- How does that relate to this topic?

- Share how . . . . . relates to this topic.

To re-examine

- How does this apply in this situation?

- What is it about that idea that you like?

- Please expand on the appeal of that idea.

- Why do you think that the team responded so negatively to that proposal?

- You said it was a negative response. Please share more about the message you received.

- How could you make what you just said easier for me to hear?

To explain

- In what way does that apply here?

- What do those have in common?

- What impact are you experiencing?

- How does that affect what is happening?

Following are some examples of probing for more information hinging on words or phrases previously expressed

- You’ve said respect a few times. Please expand on that further

- Respect. Tell me what that means.

- You mentioned fairness. Share what fairness means to you.

- A walk in the park. Please give me more information about what that entails.

Reflecting

A critical part of listening actively involves reflecting back to the speaker what the listener has heard or seen in terms of body language and behaviour related to content, feelings, or both. The purpose of reflecting is to confirm understanding between the individuals.

There are four kinds of reflecting skills: paraphrasing to reflect content, reflecting feelings to acknowledge emotion, empathizing to connect content and feeling, and summarizing to confirm and cement the understanding.

Paraphrasing Content

To paraphrase, the listener restates, in his or her own words, the content of the speaker’s message. The paraphrase should be concise but still contain the essence of the message.

A paraphrase enables the listener to confirm what he or she has understood the speaker to say. This provides the speaker with confirmation of being heard and an opportunity to correct any misunderstanding.

When paraphrasing, it is important for the listener to be as accurate as possible and resist any temptation to

- augment by adding information,

- diminish by eliminating essential content, or

- editorialize by adding personal opinion.

To introduce a paraphrase, try using starters like these:

| “Tell me if I have it straight so far . . .” “So what you’re saying is . . .” “If I understand correctly, this is what you’re telling me . . ” “Do I understand you to say . . .” “So for you it’s about . . .” |

The previous introductory phrases prepare the other party for your interpretation of his or her message. While you want to be accurate when you paraphrase, it isn’t disastrous when you don’t get the message exactly right, because you have shown your genuine attempt to understand and this gives the speaker the opportunity to clarify.

Reflecting Feelings

“Putting feelings into words has long been thought to be one of the best ways to manage negative emotional experiences. Talk therapies have been formally practiced for more than a century and, although varying in structure and content, are commonly based on the assumption that talking about one’s feelings and problems is an effective method for minimizing the impact of negative emotional events on current experience.” Lieberman, et al.

What we may have known instinctually – that talking about our feelings is helpful – is also borne out in neuroscience. Lieberman, et al. show through fMRIs that affect labeling (naming feelings) “disrupts the affective responses in the limbic system that would otherwise occur in the presence of negative emotional images”. That is, when we name the feelings we feel, we feel them less and can do something about them. Dr. Dan Siegel, a pediatric psychiatrist, pioneer in interpersonal neurobiology, and mindfulness expert calls this process “name it to tame it”. In a conflict conversation we can use this for ourselves as well as with others experiencing difficult emotions.

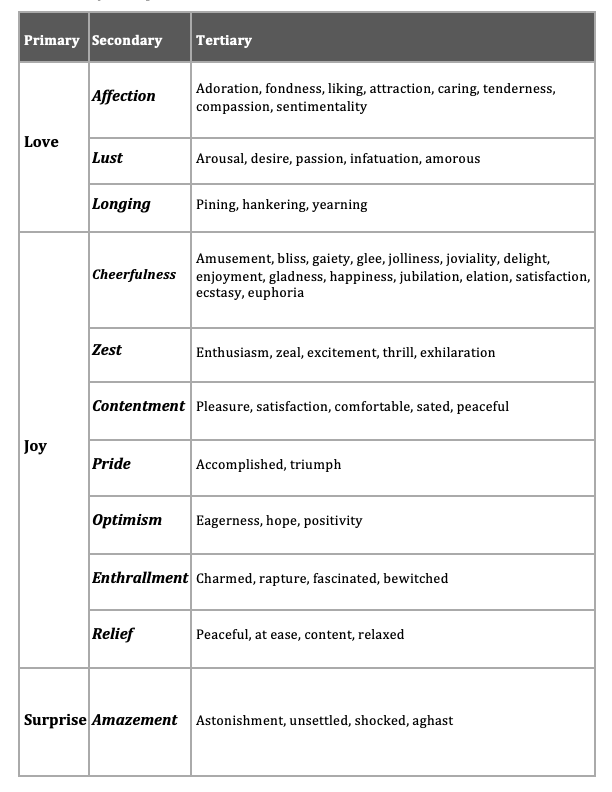

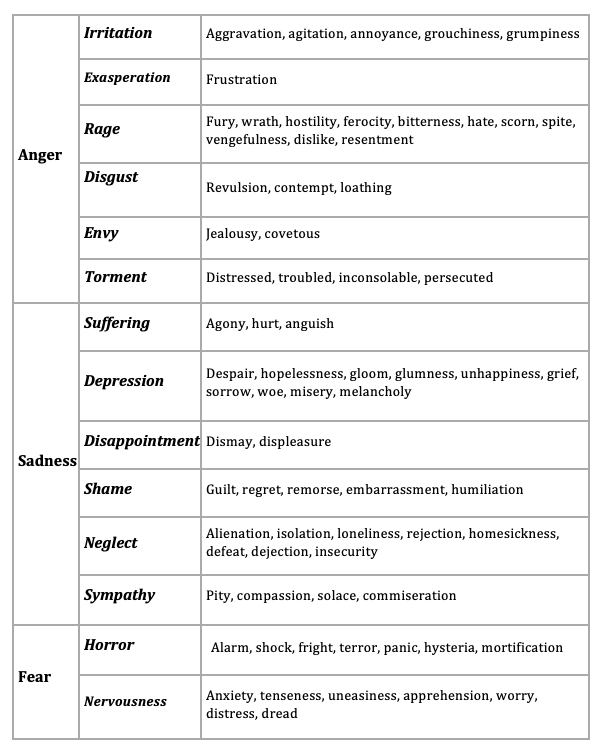

Ivey, Ivey, and Zalaquett suggest that “understanding underlying feelings leads to emotional regulation with clearer cognitive understanding and behavioural action”. Having emotions and feelings accurately reflected back to us can have a calming effect and helps us to feel understood. Remember, a good emotional vocabulary is essential to accurate reflection of feelings. We do not only feel glad, mad, sad, scared, disgust, and surprise (the primary emotions), we also experience a vast range of social emotions, such as sympathy, embarrassment, guilt, shame, pride, jealousy, indignation, etc.

Emotions are complex. Many can be positive or negative (e.g., in the face of injustice, anger may spur us to action, while hope may breed complacency). Also, people can experience seemingly competing emotions at the same time (discrepancy). So, it is not about judging the feelings as good or bad or appropriate, but about acknowledging them, so they can be understood.

When reflecting feelings, the listener identifies the emotions being perceived, both verbally and non–verbally and feeds them back to the speaker. Attend to the emotional/feeling word you hear, as well as the implied feelings that are unspoken, or delivered through context and nonverbal cues. To be most effective, the emotions should be described with feeling words that match the intensity of the emotion being demonstrated, be reflected in the moment, and in present tense.

| You sound excited. You look like you’re happy today. You seem sad. Sounds like you’re really disappointed. It looks like you are surprised to hear that. You are angry about… |

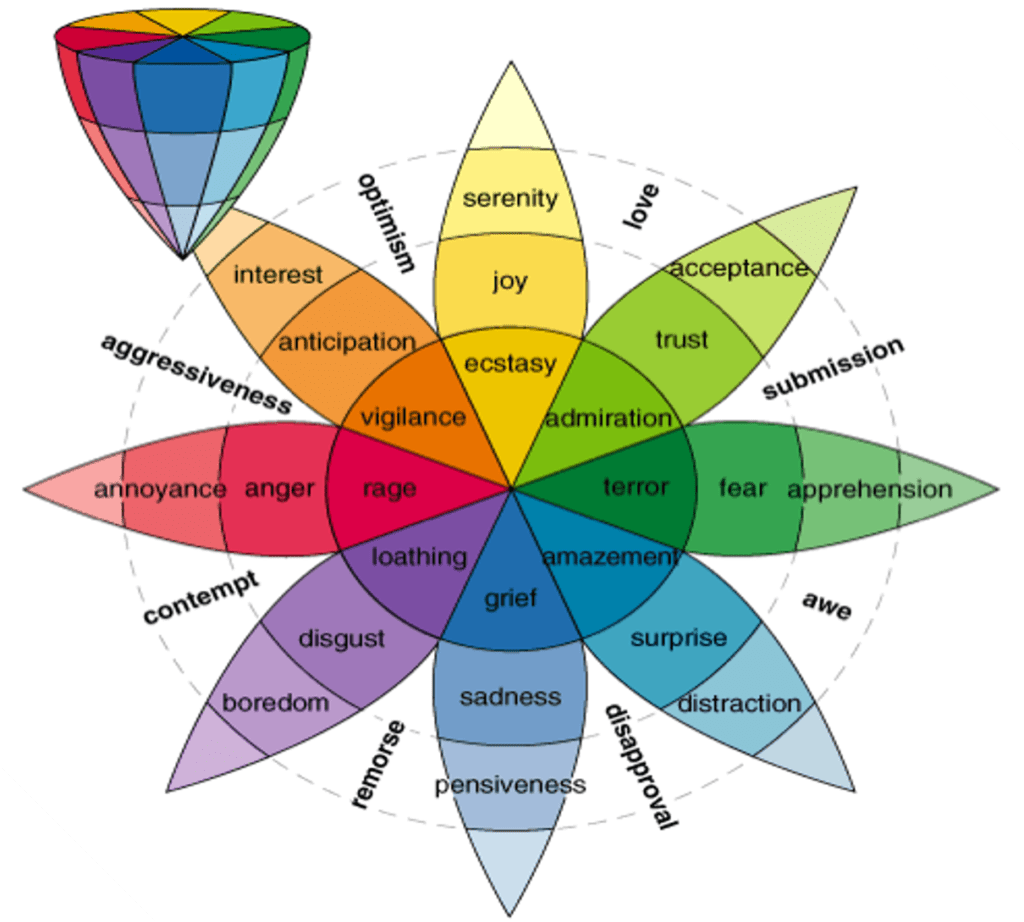

Theory: Wheel of Emotions

Robert Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions, created in 1980 depicts in 3D the intensity of eight basic emotions.

Emotions by Groups

Empathy

The purpose of making an empathic response is to connect the feeling and content being expressed by the speaker and reflect your understanding using your own words. So use this skill when the speaker needs to be heard and needs to have his or her experiences acknowledged.

Empathy requires one person to perceive that another person (in this case, you) understands him or her. Therefore, it is very important that your verbal and nonverbal behaviours are congruent: that they are sending the same message.

You can increase rapport with the other person by matching tone of voice, inflection, facial expression, or body position. You can also use language that is similar to his or hers but different enough to be true to who you are.

Being empathic does not mean you are agreeing with the other person, but rather that you understand the situation from his or her perspective.

Effective Approach

Here are the steps to follow:

- Reflect when you have a fairly clear idea of what the other person is feeling and why. These phrases will help you form an empathic response:

- From your point of view then . . .

- So it seems to you . . .

- Then in your experience you think . . . and, therefore, you’re feeling . . .

- It sounds like you feel . . . because . . .

- Then you think . . . and, as a result, you feel . . .

- You really seem to be saying you’re feeling . . . because . . .

- Clarify or Explore when you are having some difficulty recognizing what the other person is feeling and why. In these situations, you might wish to be tentative with your empathic response. Useful phrases include the following:

- Could it be that you’re feeling . . . because . . . ?

- I wonder if you’re thinking . . . and so you’re feeling . . . ?

- Does it sound reasonable that you are feeling . . . because . . .?

- I’m wondering if what’s going on for you is you’re thinking . . . and so you’re feeling . . . ?

- You appear to be feeling . . . because . . . ?

- Perhaps you’re feeling . . . because . . . ?

However you choose to begin your response, remember to always refer to both the feeling and the content to confirm understanding of the link between them for both you and the other person.

Ineffective Approach

Here is a list of some common errors that can be made when you are attempting to empathize:

- minimizing the feeling, such as saying “You’re a bit upset” when someone is furious

- assuming the underlying feeling rather than learning what it is, such as saying “You’re upset that she got the job you wanted” when nothing about being upset was mentioned

- using jargon unfamiliar to the other such as saying “You’re ambivalent ” to a 15-year-old

- repeating the same feeling word over and over

- not acknowledging content fully, such as saying “You’re angry about that.”

- reflecting back the same words that have been spoken rather than choosing a synonym that shows you understand

- implying your agreement by omitting qualifying phrases like “from your perspective” or “the way you see it” and instead saying something like, “So the boss is an idiot.”

- using empathic responses too often making them become trite rather than meaningful

- challenging the validity of the statement or feeling, such as saying “You’re angry because I didn’t call first?”

When applying empathizing skills, listeners use their own words to reflect both the content and the feeling they understand from the speaker’s message. An empathic statement is the tool that links the feeling and the content to clarify the connection for both the listener and the speaker.

The common formula for an empathic response is:

“You feel (emotion) because (the experience or behaviour that gave rise to the feelings).”

For example….

“You feel hurt because you didn’t receive a call after she left.” (experience)

“You feel annoyed with yourself because you didn’t do anything about it.” (behaviour)

“You feel guilty because she put her pride aside and asked you directly for help and you didn’t even answer her.” (experience and behaviour)

Expressing empathy does not mean that the listener agrees with the speaker, or has shared a similar experience and knows what it feels like, but rather that he or she understands the situation from the speaker’s perspective. It is often described as walking in someone’s shoes or seeing through someone else’s eyes.

Avoid giving advice, even when it is asked for directly. Instead, respond by reflecting feeling and content. Empathy can also be conveyed through tone of voice and body language.

| For example … | |

| “I don’t know what to do. If you were me, how would you handle it?” | |

| Empathic response | “You sound confused about what decision you should make.” |

“I’ve got some super news. That company we hoped would bid on our contract came in with quite a reasonable estimate. That means we can hire them and get quality work for a moderate price.” | |

| Empathic response | “You’re excited and pretty hopeful that by accepting their bid, we’ll be able to not only get the standard of workmanship we’ve been wanting but we’ll be able to do it within our budget.” |

Summarizing

To summarize, the listener provides a brief restatement of the main themes and feelings the speaker has expressed over a longer period of conversation. This provides an opportunity for both the speaker and the listener to confirm accuracy, to make sure nothing important has been overlooked, and to create a sense of forward movement in the discussion.

For example, if in a conversation one person says …

“When we went to the movie, we found the cost to be higher than expected – it was a complete rip off! But there we were, with two small boys who were counting on seeing the movie right then, not to mention who were also talking about popcorn and pop. We only had the money their mom gave us for babysitting and the movie, which left us between a rock and a hard place. If we didn’t live up to their mom’s promise of a movie, the boys would be disappointed, but if we did live up to her promise, we wouldn’t get anything for babysitting.”

| Summary response | “When you arrived at the movie, you were really frustrated to discover the cost to be more than you’d been given for tickets and snacks. It was a hard choice between disappointing the boys and giving up your babysitting money.” Or “At the movie, you found yourselves in a really tough spot – whether to spend all the money for tickets and refreshments, and take none for babysitting, or to forfeit something and upset the boys.” Or “You were really upset that you couldn’t afford to give the boys the outing as promised unless you didn’t take any payment for babysitting.” Or “The cost for the movie tickets was going to be way more than expected which meant something had to go – tickets, treats, or babysitting money.” |

As you see in the example, there are several ways the most important points and feelings can be summarized.

Reframing

People often indicate what they want by stating what they don’t want. As a result they tend to use negative, attributive, and oppositional language to describe their experiences or thoughts. These language patterns and positioning strategies keep them focused on the problem, often in a blaming or judgemental frame of mind, and unable to move forward.

Reframing is a skill that involves restating someone’s words in a way that refocuses the statement from negative to positive. It identifies what is not wanted (underlying concern or fear) and replaces it with what is wanted (unmet need). For instance, it takes a fear or worry (negative) and turns it into a need or hope (positive). It is best expressed using interest language: changing concerns and fears into hopes, values, beliefs, and needs. For instance, a reframe may begin with the following phrases:

- So you value . . . . .

- Your priority then is . . . . .

- What you hope for is . . . . .

- What matters to you is . . . . .

Reframing also has the effect of moving the focus from the past to the future, what was a negative thought, feeling, or experience in the past becomes something positive to look forward to or strive for in the future.

Reframing may be done as a stand-alone comment or may immediately follow a paraphrase or empathic statement. If the person with whom you are interacting is exhibiting a high level of emotion, you may first need to empathize to reassure them that you understand what they are saying and feeling.

Similarly, if the individual seems worried that he or she is not being understood correctly, or you are unsure of whether you understand correctly, you may need to paraphrase first to clarify what you understand is his or her perspective.

Once this reassurance or clarification has happened, he or she will then be able to listen to what you are saying in your reframe.

Consider the following examples of reframing….

| Statement | Reframe |

| “I hate it when you drive so fast! I think you’re being totally irresponsible! I’m sure we’re going to have an accident!” (underlying concern/fear – dangerous driving) | Reframe #1: “Sounds like you really need to feel safe when we’re driving together.” (unmet need – personal safety) Reframe #2: “Sounds like you’re very frightened by my driving habits (empathic statement) and you’d like to have confidence in my ability to keep us safe.” (unmet need – driver trust, personal safety) |

| “I think it’s terrible the way the cars roar down this street all the time! Those drivers just don’t stop to think about how dangerous it is for everyone who lives here, especially the kids.” (underlying concern/fear – traffic danger) | Reframe #1: “It’s really important for you to know that the local children are safe on the street.” (unmet need – children’s safety) Reframe #2: “You’re very concerned about all the traffic going by (empathic statement). The safety of your neighbourhood, especially the neighbourhood children, is a high priority for you.” (unmet need – safe neighbourhood) |

References:

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s Consequences. SAGE publications.

Hofstede, G. Dimensions of National Cultures http://geerthofstede.com/dimensions-of-national-cultures Accessed: January 2016

Ivey, A. E., Ivey, M. B., & Zalaquett, C. (2014). Intentional Interviewing and counselling: Facilitating client development in a multicultural society (9th Edition) Belmont, CA: Thomson

Oetzel, J. G., Ting-Toomey, S, & Yee-Jung, K. (2002). Interpersonal Conflict in Organizations: Explaining Conflict Styles via Face-Negotiation Theory. Communication Research Reports, 20(2), 106-115. d

Wong, R. Y.-M. , & Hong, Y.-Y. (2005). Dynamic influences of culture on cooperation in the prisoner’s dilemma. Psychological Science, 16(6), 429-242. Doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01552.x

Yang, C., LaRoche, L., Leading Multicultural Teams, MultiCultural Business Solutions, http://www.mcbsol.com/pdf/Resources_Article_Leading_Multicultural_Teams.pdf, Accessed: March 2016

Crawley, D. The Five Levels of Listening (How to be a Better Listener). http://www.doncrawley.com/the-five-levels-of-listening-how-to-be-a-better-listener/

Ivey, A. E., Ivey, M. B., & Zalaquett, C. (2014). Intentional Interviewing and counselling: Facilitating client development in a multicultural society (9th Edition) Belmont, CA: Thomson

Lieberman, Matthew D., Eisenberger, Naomi I., Crockett, Molly J., Tom, Sabrina M., Pfeifer, Jennifer H., & Way, Baldwin M. (2007). Putting Feelings Into Words: Affect Labeling Disrupts Amygdala Activity in Response to Affective Stimuli.(Author abstract). Psychological Science, 18(5), 421-428.

Dr. Nichols, R.. On Listening, Interview by Rick Bommelje, Listening Post, Summer 2003, Vol 84.

Rogers, C., (1951). Client-Centred Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications, and Theory. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin), cited in: Bolton, R. People Skills. Simon & Schuster. New York, New York. 1986. Print.

Schulz von Thun. “Introduction to the Inner Team Model”. Chapter I: In Talking to Each Other. The Inner Team and Situation Specific Communication. Renbeck, Germany: Rowohit Taschenbuck Vedag. 1998.

Siegel, D., (Published December 8, 2014) Dan Siegel: Name it to Tame it. Accessed: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZcDLzppD4Jc[TB14]

© 2014 ADR Institute of Alberta

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, or any information storage and retrieval system. Permission is not given for preproduction of the materials for use in other published works in any form without express written permission from the ADR Institute of Alberta (“ADRIA”), with the exception of reprints in the context of reviews.