What is ADR?

ADR can stand for Alternative, Appropriate, or Adaptive Dispute Resolution. These different definitions are used interchangeably throughout the ADR community to describe the different interpretations and expectations placed on dispute resolution processes.

Alternative has the longest history of usage (particularly in academia), and is used to suggest that ADR is an alternative to litigation embracing a variety of practices including: mediation, negotiation, facilitation, arbitration, consensus decision making, and restorative practices.

Appropriate is used as a definition to highlight the ADR community’s aim of being collaborative, respectful, and considerate of everyone’s view. Furthermore, it speaks to selecting the dispute resolution option that is most appropriate for the parties and their individual circumstances.

Adaptive is used when emphasizing the creative elements of ADR; the ability to come up with solutions not traditionally available through processes like investigation, litigation, and the courts. You will find that Alternative and Appropriate are the terms used most commonly by the ADR Institute of Alberta and its members.

Definitions

| Conflict | opposition between two or more beliefs, perspectives, or values. It occurs when our sense of who we are, what we believe, or how we see the world has been challenged or compromisedor when there is incongruence in one’s own perspective, behaviour, and values. As such, conflict is not necessarily good or bad. |

| Dispute | usually a short-term disagreement that is based on resolvable issues and, again, is not necessarily good or bad. |

Although conflict and disputes can occur independently of one another, they can also be connected. “One way to think about the difference between them is that short-term disputes may exist within a larger, longer conflict. A similar concept would be the notion of battles, which occur within the broader context of a war”(Spangler, 2003), just as disputes can occur within a larger conflict. Disputes, however, can also occur within an otherwise harmonious environment.

Both disputes and conflict can be complex. In fact, they resemble an iceberg in that only a small part of any dispute or conflict appears above the surface or water line.

Conflict is a common and natural occurrence in our lives and surfaces at work, at home, within the community, or between strangers on the street. Conflict, as a subject of study, is complex because it can be a quick and short-lasting burst between normally friendly individuals, a long standing, deep rooted dispute among several teams at work, or even generations-old animosity related to geographic boundaries, cultural traditions, or religious beliefs. It can be related to tasks, relationships, societal norms, culture, or any other topic or situation imaginable. It could be said that where there are two people, there is the possibility of conflict, but even that is too simple. Where there is one person, there is opportunity for conflict because we often have to balance our needs, desires, concerns, and wants with conflicting values, resources, and emotions.

| Expanded Definition of Workplace Conflict | “The word “conflict” is commonly used in everyday speech to label various human experiences, ranging from indecision to disagreement to stress. To be correctly understood as a “conflict,” a situation must contain each of the four elements of our definition: a condition between or among workers whose jobs are interdependent, who feel angry, who perceive the other(s) as being at fault, and who act in ways that cause a business problem.” – Daniel Dana |

Notice that this definition includes feelings (emotions), perceptions (thoughts), and actions (behaviours). Psychologists consider these three the only dimensions of human experience. So, conflict is rooted in all parts of our human nature.

Conflict can be costly to both an individual and at an organizational level. When a conflict is ongoing, some of these costs can include: loss of time, loss of human resources, loss of financial resources, damage to relationships, damage to trust, and a loss of productivity.

We usually view conflict as a negative thing, which can lead us to avoid potentially conflict-causing situations. However, handling conflicts effectively is an opportunity to strengthen relationships and build respect.

ADR Processes and Conflict Management

As mentioned already, conflict is one of the most common occurrences in our lives, whether the conflict surfaces at work, at home, or in other relationships in which we are involved. Conflict has been with us as long as human history has been recorded, which has resulted in conflict management evolving through the years (Persinger, 2004).

ADR had its beginnings in the 1970’s, although it can also be traced back to the workings of Marx in the early 1800’s (Sandole, 1993). As with most successful processes, it grew from a trial and error approach and resulted in the emergence of a number of programs that fall into two categories: those that are self-managed and those that are either facilitated or adjudicated by a third party.

Definitions

| ADR | Alternative, Appropriate, Adaptive Dispute Resolution an acronym that refers to several methods of resolving conflict outside traditional legal and administrative forums. However, because ‘alternative’ tended to suggest that the legal community and ADR practices were either/or choices, some professionals prefer to refer to it as Appropriate or Adaptive Dispute Resolution, implying a more situational or creative approach to conflict management. |

| Position | a solution that meets a person’s own needs, often expressed as demands or conditions beginning with these terms: I want… I don’t want… You better…or else… We have to… You will… You have to… I will not…. It needs to be… |

| Example: | “I’m not paying for the repairs because they weren’t done to my satisfaction.” |

| Issue | the topic about which parties disagree and which forms the basis for the dispute. What needs to be discussed/resolved. Issues can be identified by listening to the position(s) of the party/parties. |

| Example: | the invoice for the repairs and workmanship |

| Interests | a collection of needs and motivators, which a person must have met by any resolution or agreement. Interests are any expression of priorities, expectations, assumptions, concerns, hopes, beliefs, fears, values, or needs. |

| Understanding-based OR Interest-based | any form of discussion that focuses on the parties’ priorities, expectations, assumptions, concerns, hopes, beliefs, values, fears, or needs rather than on the parties’ rights, entitlements, positions, or solutions. |

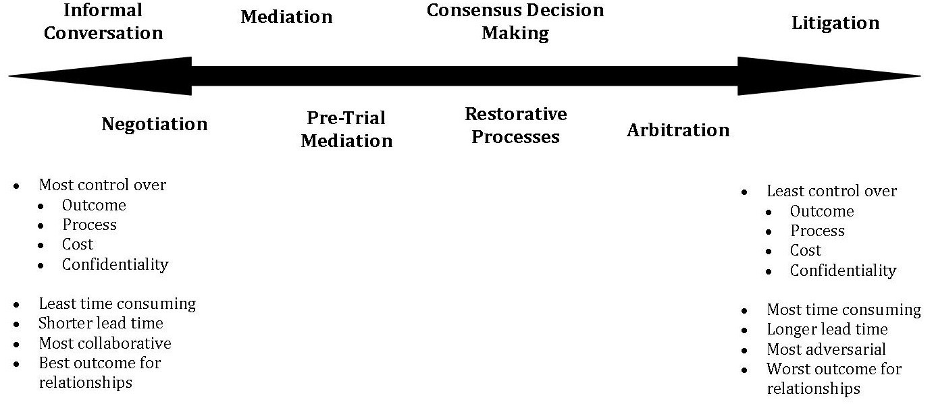

ADR Spectrum

As ADR evolved and interest-based processes became more widely used and researched, the scope of dispute resolution approaches broadened and expanded. With the evolution of interest-based processes, a number of key foundations were identified:

- Focusing on needs and interests.

- Differentiating between interests and positions (refer back to definitions).

- Emphasizing the importance for parties in conflict collaborating to resolve the issues in a mutually satisfactory manner together.

ADR processes range from …

- Self-help, self-directed interactions to third party decision-making processes.

- Low expense, structured meetings to costly, formal procedures.

- Short duration, structured, facilitated discussions to long, structured, facilitated discussions that could occur over months.

- Relationship enhancing experiences to potentially relationship damaging experiences.

Negotiation

(does not have to be a dispute)

In a negotiation process, parties communicate directly with each other and make their own decisions. The outcome is likely a contract or an agreement that summarizes the parties’ resolutions or commitments around the issues at hand. Negotiation can be positional, which takes the form of “I want ……… no matter what you want,” and that results in a win-lose situation. Negotiation can also be understanding-based, during which skilled parties look for each other’s underlying interests, share their own interests and work toward a win-win resolution.

Negotiation can stand alone as a process, but the knowledge gained through understanding-based negotiation study and practice contributes to the possibility of greater growth in mediation and complex multi-party consensus building.

Advantages:

- Can be quick, informal and private.

- Parties communicate with each other.

- Counsel or other third parties optional.

Disadvantages:

- If parties are not skilled might not reach the best win-win agreement or can turn into positional struggle.

- No guarantee of success.

- Parties must want resolution.

Mediation

(also called facilitated dialogue)

In an understanding-based mediation process, a selected, skilled, and impartial third party facilitates a discussion between disputants that allows them to make their own decisions and solutions in relation to issues and conflict. The mediator is a process manager, who, using facilitation and collaborative dialogue, guides parties through a structured process.

Advantages:

- Private and confidential if parties agree.

- Legal representation is not required; in some mediation cases legal advice is encouraged.

- Even if an agreement is not reached, parties can have better understanding of the situation and each other’s perspectives.

- Can result in creative solutions.

- Can be less costly than Arbitration or Litigation.

- Mutually agreed upon resolution.

- Possibly binding agreement.

- Parties communicate with each other.

Disadvantages:

- Participants must agree to mediate.

- If parties need an outside decision this process may not work.

- Agreements may need to be vetted by a lawyer in order to become binding.

There are different types of mediation such as narrative, transformative and evaluative, in addition to collaborative or understanding-based mediation taught by ADRIA. Other variations include Shuttle Mediation or Conciliation in which the mediator facilitates a process with the parties in separate rooms.

Pre-Trial Mediation

Pre-trial mediation is a mandated process that, like any other mediation, involves selected, skilled, and impartial third party facilitators helping litigants make their own decisions and solutions in relation to their lawsuit. While the mediators still act as process managers, the litigants are not initially voluntarily a part of the process. More specifically, parities may request mediation at the time they file a Claim or Dispute Note. However, in the majority of cases, it is the Court that directs parties to mediation.

Advantages:

- Legal representation is not required.

- Confidential if parties agree.

- Parties can discuss matters that would not be permissible in court yet have a bearing on the matter in dispute.

- Agreement has same legal standing as a judge’s decision.

- Parties can arrive at a mutually beneficial agreement that the court could not mandate (be more creative).

- Parties communicate with each other.

Disadvantages:

- Cannot be used for precedent setting cases.

- Time bound.

Consensus Decision-making

(or Collaborative Decision-making or Multi-Stakeholder Engagement)

Consensus decision-making is a conflict-resolution process that is used to settle difficult, multiparty disputes or to help multi-party groups share information and formulate plans. Since the 1980s, consensus decision-making has become widely used in the environmental and public policy arena, but it also can be a useful dispute resolution process whenever there are multiple parties involved in a complex dispute or conflict. The process allows various stakeholders (parties with an interest in the problem or issue) to work together to develop a mutually acceptable and beneficial solution.

Like the running of a town hall meeting, consensus decision-making is based on the principles of local participation through the development and ownership of decisions. Often as the group comes together, they design the process to be used, identify the parties needing to be present, share perspectives on interests, and brainstorm options and resolutions.

Ideally, the consensus reached will meet all of the relevant needs and interests of the parties. While everyone may not get everything they initially wanted, consensus is reached when the parties are able to develop outcomes or solutions that are acceptable to all. It can also be used to help groups prevent or mitigate disputes by encouraging them to work together.

Advantages:

- Can achieve sustainable results that are supported by diverse stakeholders.

- Parties communicate with each other.

- Mutually agreed upon resolution for all stake holders.

Disadvantages:

- Takes time and effort.

- Process can be hijacked by special interests.

- Difficult to engage, get full participation.

Restorative Processes

Restorative processes include many different practices. One of them is restorative justice, which is a non-adversarial, community-generated, sanctioning process that brings the justice of the accused back to the community level. Specifically, the values of restorative justice challenge traditional goals of intervention, in that they move the focus from punishment of an offender to repairing the harm done as much as is possible. Where the current judicial system centers on the victimizer, restorative justice includes the victimized in order to make sure all affected parties have a voice and a meaningful role in crafting the solution. Restorative justice requires a change in how the criminal justice system and the community interact, in that the community plays a much larger and more active role in promoting safety and justice. Restorative processes also include circles in schools to handle bullying and as well as in businesses and other organizations. Circles can be proactive or reactive and can be used to repair harm as well as handle conflict.

Advantages:

- Heals and restores rather than punishes and victimizes.

- Can bring about reintegration.

- Deep exploration of events, emotions and interests.

Disadvantages:

- Takes time and willingness.

Arbitration

In the arbitration process a jointly selected or a contract legislated third party receives statements and arguments of both parties and acts as the decision maker by writing up what is called an award. The arbitrator’s decision, which can be influenced by but is not bound by precedent, is final and binding.

Arbitration functions within the framework of the law but outside the formal legal system. Each case is decided according to the merits of the individual case.

While the history of arbitration is grounded in the commercial context, over the past 10 years Canada has seen arbitration used more widely in a variety of disputes including family issues, wrongful dismissals, shareholder agreements, buy-sell agreements, construction projects, commercial leases, and many other types of issues. Arbitration is also often used in disputes arising from international trade. Arbitration is governed by the Alberta Arbitration Act and the award becomes a public record within the legal system.

Advantages:

- Is governed by legislation.

- Decision is final and binding.

- Arbitrators are usually specialists in the area being arbitrated.

- Less costly and less complex than litigation.

- Legal representation not required.

Disadvantages:

- Does not deal with relationship issues.

Litigation

The Province of Alberta administers three courts: the Court of Appeal of Alberta, the Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta, and the Provincial Court of Alberta. The Provincial Court is comprised of civil, family, traffic and youth. All criminal matters start in Provincial Court. The Court of Queen’s Bench is the Superior Trial Court and handles civil and criminal matters as well as appeals from decisions of the Provincial Court. The Court of Queen’s Bench also handles Surrogate Matters, which are matters of probate and administration of estate. The Court of Appeal hears appeals from the Court of Queen’s Bench, the Provincial Court and administrative tribunals, and provides its opinion on questions referred by the Lieutenant Governor under the Judicature Act.

Litigation begins with a claim or charge that is filed at a court either by an individual or by an individual’s legal representative (agent or lawyer). An appointed judge supervises the formal judicial process and acts as the decision maker. Often in the court process the parties do not communicate directly with one another; rather, they speak through their lawyers. The structure is highly formal, and the judge not only has full authority to make a decision for the parties in conflict or the issue at hand, but the obligation to make a decision. The judge’s decision is final and binding and is filed as a public record within the judicial system.

There is little to no privacy and there are often witnesses, members of the public, and other professionals in attendance.

Advantages:

- Decision is final and binding.

- The dispute is always resolved.

Disadvantages:

- Enforcement of ruling can be problematic.

- Process is time consuming and often costly.

- Little or no privacy during trial, decision is filed as a public record.

- Not voluntary.

- Highly formal.

- Results focused, therefore relationships can be in jeopardy.

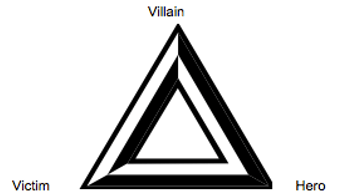

Theory: Drama Triangle

The roles people play in conflict, and their shifting relationship to each other, have been described as being part of a Drama Triangle. This suggests that the roles individuals undertake in conflict mirror what is depicted in drama, particularly fables, legends, and fairy tales. The theory is that the stories we heard as children don’t just help us understand societal norms, they inadvertently provide us with behaviour models that contribute to conflict.

Gary Harper describes the three roles that make up the Drama Triangle as the Villain, Victim and Hero. All roles are interchangeable, and a person may play each of them at one time or another in the same conflict.

The victim, for instance, can move into the hero role by deciding to “stand up and do right thing.” (Self-righteousness can move the victim to hero role very quickly). The victim can also move to the villain role by demonizing the person s/he is in conflict with, by trying to “get even”, by trying to build his/her camp of supporters, by trying to hurt the other party.

The hero and the villain share similar characteristics and whether you see them as hero or villain depends on your perspective, your world view, who wins, the values of your people, cultural lenses, and the context of the situation. For example, Robin Hood could be seen as a hero for stealing from the rich to benefit the poor. Others might see him as nothing more than a common thief and scoundrel.

As Harper explains, “In a different context, Robin Hood would have done 5 to 10 years of hard time for extortion and armed robbery. Instead, his actions are not only excused but revered in legend because of his noble cause and earlier mistreatment by the evil Sheriff. Similarly, Jack (of Jack and the Beanstalk fame) made his reputation through trespass and burglary, though these acts are seen as heroic because the giant was mean.”

For conflict to be resolved, parties in conflict need to move off the drama triangle. This is accomplished by ensuring they have an opportunity to share their perspective and feelings, and for you to do the same. It means separating the people from the problem, and replacing judgment with curiosity. It means uncovering their underlying needs, and sharing yours. It means helping them realize there may be more than one way (solution) to meet their underlying needs that also take into account your needs.

| Qualities | Behaviours | Payoff | Price | |

| Victim | Innocent Powerless Hurt Helpless Hopeless | Blaming Complaining Passive Demonizing Self-righteous | Attention in form of sympathy. Don’t have to take responsibility. Being “right”. | Self-esteem eroded. Drive people away. |

| Villain | Evil Arrogant Controlling Sneaky Uncaring | Takes Deprives Hurts Attacks Destroys | Get what they want. Win the day. See themselves as misunderstood heroes. | Despised |

| Hero | Strong Noble Righteous Courageous Selfless Risk-taker Self-reliant | Takes charge Rescues Takes (back) Slays Attacks Punishes | Power over. Ego gratification. | Takes responsibility for others’ problems – others aren’t empowered. Moves to villain role if it doesn’t work. |

Typical Conflict Stories

Along with the three typical roles in conflict, there are also two types of stories you can tell. One story makes you the hero and allows you to justify various feelings and concerns. The other allows you to continue to see others as villains, or, at least, as incorrect, wrong, or just not as good a person. One of the ways you can ensure you are able to move yourself out of typical conflict roles and behavior is to reduce the defensiveness you might not even recognize you are feeling.

Example:

| Situation | Your Story |

| Someone might be late meeting you for lunch, for the third time. | They are irresponsible and unreliable. |

| You are late for lunch again, for the third time. | You are extremely busy at work and so reliable, you won’t leave work until every task that can be done is done. |

The Other’s Perspective

Choose a conflict and contemplate the following:

What is my story:

What is the other person’s story:

What is a possible alternative story:

Introduction

This first part of this course is all about you so enjoy this part of the journey. Responsibility for communicating in a more skilled way with those with whom you are in conflict will begin very soon.

You will get the most out of this course by allowing yourself to be in a state of curiosity and a place of learning. The classroom is a place where laughing is encouraged, safety is a requirement, and discovering that you know less than you thought you knew is celebrated.

Welcome to an opportunity to truly understand who you are in conflict, so you can choose how to respond rather than learning how to recover from reacting.

Conflict

Conflict leads to stress and a freeze, flight, or fight reaction. It can also lead to a very strong tendency to jump in and solve a problem. We take our first very important step toward resolution when we stop reacting, talking, and solving, because solving a surface problem is not necessarily the right approach to resolving conflict.

A far better approach, depending on circumstances, is to find out what is motivating others or causing them to have a different perspective from your own. Communicating (asking, listening, talking) plays a significant role in moving toward understanding. Dealing with conflict requires curiosity, effective communication skills, and vision (the ability to see things as they could be) and can lead to positive results.

Understanding Conflict

In conflict, people are in one of two modes: moving away from something or moving toward something. When we hear a message we don’t like, our reptilian brain, including the brain stem and the cerebellum, reacts and we respond through flight, freeze, or fight. In The Joy of Conflict Resolution, Gary Harper says, “when we are out of control with rage, it is our reptilian brain overriding our rational brain components”. Our reptilian brain also keeps our bodies functioning by making sure we breathe, that our blood flows through our veins, that we digest our food, and so on. To mix metaphors, it’s our automatic pilot.

Our cerebral cortex, on the other hand, integrates our sensory impulses and allows us to function intellectually. It allows us to have options and to choose our responses to situations. Going back to our airplane metaphor, it allows us to take back the control of the plane from the automatic pilot.

Generally speaking when people are moving away from conflict, they are reflective problem solvers. If they move toward conflict, they are more likely to be the kind of person who works toward goals, a visionary. Moving away from conflict or pain is much more familiar to us. It’s harder to work ahead to the unknown than it is to move away from the past.

Most people are able to describe how family or friends respond to conflict, but are far less accurate when they describe themselves. Determining your conflict style(s) is important in order to understand more about your reactions so you can, in turn, build on strengths, recognize unproductive patterns, and be able to choose how you will respond to conflict in various situations. We will use The Kraybill Conflict Style Inventory, Style Matters, to determine your individual conflict style and how best to manage it.

Conflict Styles

There are five commonly used styles of handling conflict, placed on a scale in terms of satisfying your own agenda or in terms of satisfying the goals of others. Typically, you will rely on only one or two styles, though all styles have their uses depending on the situation.

Directing

There is a high focus on own agenda and a low focus on the relationship. This conflict style can also influence others involved to be directive as well. Competitive tactics can include: authority, persuasion, threats, force, intimidation, and suppressing or disguising the issue.

This style is useful in emergency situations, when a group needs a firm leader in a high-pressure situation, or to protect yourself in an unfair situation. However, using a directive style frequently can lead to trust issues, a failure to resolve the conflict, and an increase in stress on both yourself and others involved, which can lead to health problems and low morale.

Avoiding

There is a low focus on own agenda and a low focus on the relationship. It is the most common conflict style, especially in individuals who have been brought up to believe that conflict is a bad thing. Avoiding tactics can include: leaving the situation, withdrawing mentally, changing the subject, acting like the problem doesn’t exist, minimizing the problem, blaming others for the problem, and crying or yelling to attempt to derail the situation.

This style can be useful to allow people time to reflect on the conflict and act appropriately, or in situations where either the situation or the relationship is doing more damage being addressed than it is when left alone (like in situations that might threaten to escalate into physical harm). It can also be used in situations where people need a bit of time to process conflict before they can return to the table with a different kind of style. However, using this conflict style frequently can lead to disputes building up and exploding, issues not being properly dealt with, and a perceived loss of accountability in the person using it.

Harmonizing

When using a harmonizing style, there is a low focus on your agenda and a high focus on the relationship. A common example is when a person sets aside their own interests to satisfy the needs of the group. Harmonizing tactics include: playing down the conflict to maintain harmony, grinning and bearing it, convincing yourself it’s no big deal and not bringing up an issue, giving in to another’s demands, and taking all of the blame for a problem.

Using this style can sometimes influence the other person be more accommodating to your needs in the future, can build good faith for future problem solving, and should be used in situations where you are wrong or when you are in a potentially reputation damaging position. However, it can also lead to you feeling resentful and taken advantage of and does not lead to improved communication meaning there is a potential for repeated problems. Using this style often means the outcome of the conflict is usually not satisfactory to both parties.

Compromising

When using a compromising style, there is a medium focus on agenda and a medium focus on the relationship. Both parties must give something up to meet halfway. Compromising tactics include: splitting the difference, giving a little and taking a little, exchanging concessions, urging moderation, and bargaining.

Using a compromising style can lead to a temporary agreement, making inroads in a complex situation, can be a good backup plan if collaborating fails, and is relatively fast while building a cooperative atmosphere. At the same time the issue is not explored at any depth and usually symptoms are patched while the overarching problem is ignored.

Cooperating

There is a high focus on your agenda and a high focus on the relationship. Cooperative tactics include: working to increase resources, listening and communicating to promote understanding, inviting other views and opinions, and learning from each other.

Using a cooperative style can build relationships, improve the potential for future problem-solving, promotes creative solutions, and gain trust. However it can be very time consuming and can lead to a situation where everyone is analyzing a problem instead of working towards a solution.

Theory: Ladder of Inference

The process of paying attention to certain data and experiences because we are familiar with them, then attributing meaning to those data and experiences, developing assumptions, and coming to conclusions are steps in what is known as the Ladder of Inference. (An explanation of the Ladder of Inference is available in far more detail in The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook by Peter Senge and will be discussed in detail in the National Introductory Mediation course taught by ADRIA.)

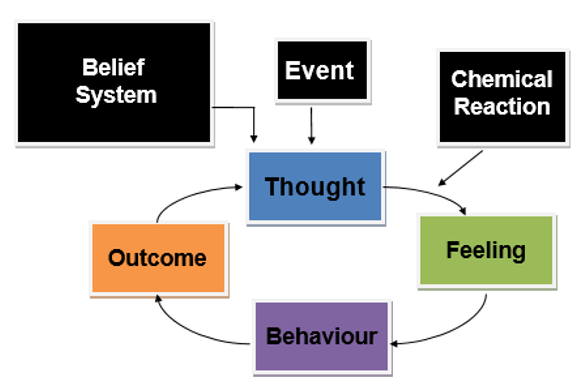

The top two steps in the ladder involve moving from our conclusions to beliefs, which in turn affect our behaviours. We must ask ourselves if something is true, if we know it’s true, and if we are absolutely sure that we are basing our knowledge on facts and data, not on assumptions. An excellent model that helps us understand this part of the process is called the Cognitive Behaviour Model.

Theory: Cognitive Behaviour Model

Shad Helmstetter, Ph.D. says it is our programming from the time of our birth that sets our beliefs. In logical progression, what we believe determines our attitudes, our attitudes affect our feelings, our feelings direct our behaviour, and our behaviour (reaction or response) determines our success or failure (consequences or outcome), all of which is indicative of how we process conflict.

The cognitive behavioural model (shown here) purports that our cognitions (acquired knowledge) affect our behaviour. For instance, if someone who thinks fire safety equipment cannot reach above the eighth floor of a building wins a trip to Hawaii and is booked into a hotel on the 12th floor, he might start having heart palpitations and be unable to sleep at night from fear. He might then change the hotel booking in order to stay on the seventh floor or below. Similarly, someone who believes she will faint in crowded places because of lack of oxygen will avoid areas where there are lots of people.

In either case, the belief might be true, but it doesn’t have to be in order for behaviour to correspond with it.

The Cognitive Behaviour Model is also known as the Think-Feel-Do-Loop.

Resolving Conflicts

Choosing the most effective way to resolve a conflict requires what Daniel Goleman and other authors in this field call emotional intelligence.

Becoming emotionally intelligent in the face of conflict requires us to be mentally cognizant in the moment, to logically intellectualize as we respond versus emotionally reacting. This is often referred to as the head or heart response.

Our beliefs, values, and attitudes provide the basis for our emotions and our thinking in a conflict situation. Integrating our patterns for dealing with conflict with our beliefs, values, and attitudes— to consciously choose appropriate behaviours and verbal responses— will profoundly enhance the potential for a positive consequence or outcome of any conflict.

The consequences will either allow us to reinforce our beliefs and attitudes about conflict or encourage us to re-examine our beliefs and attitudes.

The consequences can elicit stress or relief, cause escalation or de-escalation, or improve or diminish relationships. If we really want to change our lives, we must first change our attitudes.

Correspondingly, if we want to change the consequences in conflict, we must first examine our beliefs, values, and attitudes about conflict. Our cycle of conflict will change according to the impact and interpretation of both our negative and positive experiences with conflict.

References

Dana, D. What is a Conflict? 2001. Retrieved February 2, 2016 from http://www.mediate.com//articles/dana1.cfm

Harper, G. The Joy of Conflict Resolution: Transforming Victims, Villains, and Heroes in the Workplace and at Home. 2004. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Persinger, T. Courageous Communication. 2003. Retrieved January 21,2004 from http://www.mediate.com/articles/persingerT3.cfm?nl=43

Sandole, D. & Van der Merwe, H. Conflict Evolution Theory and Practice – Integration and Application. New Your. Manchester University Press. 1993.

Spangler, Brad and Heidi Burgess. Conflicts and Disputes. Beyond Intractability. Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: July 2003 http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/conflicts-disputes

Dana, D. (2001). Conflict Resolution. New York, NY: The McGraw Hill Companies.

Also available online: at http://www.mediate.com/articles/dana1.cfm.

Goleman, D. (2005). Emotional Intelligence. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Harper, G. (2004). The Joy of Conflict Resolution: Transforming Victims, Villains, and Heroes in the Workplace and at Home. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Kraybill, R. (2005). Style Matters: The Kraybill Conflict Style Inventory. Harrisonburg, VA: Riverhouse ePress[TB8] .

© 2014 ADR Institute of Alberta

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, or any information storage and retrieval system. Permission is not given for preproduction of the materials for use in other published works in any form without express written permission from the ADR Institute of Alberta (“ADRIA”), with the exception of reprints in the context of reviews.