Introduction

Frequently in our personal, everyday lives, we are in need of additional information in order to make choices or decisions, solve problems, or simply respond to communication from others. Almost always in our work lives we need additional information.

It is not uncommon that, in order to make decisions, we find ourselves filling in the gaps by making assumptions about individuals or situations. Particularly in situations where there are time constraints, or it is not practical or possible to access more complete information, we proceed with what we believe to be true. What we believe to be true is too often based on assumptions.

Sometimes assuming or filling in the gaps proves successful and our perceptions, assumptions, and hunches are confirmed as correct and, therefore, helpful. However, in other instances we discover that we have assumed incorrectly, and we then risk acting upon the wrong information and making inappropriate decisions. Just think for a moment just how many circumstances lead to our perceiving things differently. Here are just a few:

- recent experiences

- physical size and capability

- vantage points

- age

- comprehension

- distance

- knowledge

Depending on the level of negative impact of the resulting assumptions, we may find ourselves immersed in a conflict or supporting decisions that will not, in the long run, be of benefit.

In the course of our work world communication, it is interesting to note how often assumption or inference plays a part. During what might seem like an ordinary conversation, we find ourselves reacting more to what hasn’t been said and to what we think is intended by the verbal exchange rather than what has been said. We base our thoughts or assumptions on what we expect to happen, given our experiences, values, needs, or fears. This, in turn, might elicit an emotional reaction, confusion, or a seemingly unrelated consequence.

Definition

| Perception | The Free Dictionary defines perception as “recognition and interpretation of sensory stimuli based chiefly on memory” and “the neurological processes by which such recognition and interpretation” are affected. |

Beliefs, Values and Attitudes

As adults, one of the greatest challenges we encounter is to confront our beliefs and attitudes. Having developed as a result of individual life experiences, our beliefs, values, and attitudes influence the way we handle ourselves in conflict by providing the filter for interpretation of a conflict situation. Unless we choose otherwise, this causes us to deal with conflicts in the present just as we have dealt with them in the past. In other words, we simply react, by handling the conflict in an instinctual or habitual way.

Once we stop to realize that all people, situations, and conflicts are different and that the level of success may vary from one situation to another, we realize that handling all conflicts the same way is not always effective and does not always serve us best. There is an opportunity instead to respond rather than to just simply react.

What I can control is myself and no one else. I can choose to respond thoughtfully. When we react, we let our emotions govern our words and actions. When we logically respond, we think objectively, forcing ourselves to momentarily detach from our emotions and intellectualize about how we can appropriately respond.

In addition to questioning our own assumptions and looking for contrary evidence, an important step in responding thoughtfully is to clarify meaning and assumptions.

The roots of our belief system about conflict can be traced to our early childhood, school years, adolescence, and young adult life. Throughout our formative years, as we develop and interact with others around us, we are affected both positively and negatively by our experiences and the feedback we receive in conflict situations.

While we are very young children we are influenced by our parents, close relatives, and family friends. During our elementary school years, our circle of influence expands to include classmates, teachers, and coaches. Then, as we move through adolescence, we are significantly impacted by interaction with our peers and adult role models. As young adults, establishing our professional and personal lifestyles, our beliefs about conflict continue to be both challenged and strengthened by experiences with many others around us. We will all experience every type of conflict imaginable, along with the variations of beliefs associated with conflict.

Choice Points

Choice is what comes from realizing we have more than one option. When we refer to choice points in conflict, we are saying that there is more than one possible response to an event. Choice points are the intellectual equivalent to the physical fork in the road; they are moments when we can choose the direction in which we are about to go.

Behaviour

An outcome can change only if behaviours change and behaviours will change only if beliefs change. On his website, Robert Porter Lynch claims that “All the great problems of the world today will be solved on a foundation of collaborative innovation”.

Dr. Lynch has studied trust in organizations and created what he calls a ladder of trust (or the spectrum of trust) in organizations that illustrates how people climb up the ladder of trust (above the belt) or descend down the ladder of distrust (below the belt).

Theory: Ladder of Trust

(Also referred to as the Architecture or Spectrum of Trust)

Anything below the belt is described in terms of behaviour that destroys trust. As we move above the belt, we move to behaviours that instill trust and reflect shared values.

So what causes distrust? Lynch’s Ladder of Trust depicting behaviour, as shown below, indicates that withholding, judging, manipulating, or going for the win at the cost of another person can be seen as below the belt. As hurtful and harmful as these behaviors are to the recipients, Lynch further suggests that what underlies the “trust busting” behaviors is fear.

- Fear of being taken advantage of

- Fear of loss – control, territory, possessions

- Fear of being hurt emotionally

- Fearful insecurity of being damaged economically

- Fear of physical harm from attack or being put in a precarious position

- Fearful insecurity of being damaged physically

- Fear of looking bad – ego fear

- Fear of betrayal

- Fear of damaged reputation

- Fear of rejection or exclusion

- Fear of failure

“As human beings we aren’t wired to trust what we fear. Fear is a form of brainwashing causing people to withdraw, withhold, undermine and generate suspicion; trust does just the opposite,” says Lynch.

The following descriptions are from Lynch’s Ladder of Trust:

Below the Belt Behaviours

Assassination

In a workplace, this refers to character assassination, an often subtle and insidious form of betrayal. Betrayal creates intense emotional pain and its corrosive forces destroy teamwork, co-creativity and community. Betrayal can cause those betrayed to retreat into protective self, or to exact revenge.

Nullification

These behaviors are meant to marginalize, dismiss, or make meaningless another person. It’s when everyone else gets the email about the meeting change except you. It’s when you ask for feedback or assistance and are ignored. Nullification is destructive because it destroys trust and it thwarts a universal need for everyone to feel needed and to make a difference.

Corruption

This manifests itself as unethical behaviour, which in turn creates great distrust in the intentions and integrity of the person so engaged in corruption.

Aggression

The use of power to threaten or harm others is a sure way to create distrust. Aggressive behavior may be overt, overbearing and self-satisfying at the expense of others. The aggressor believes the best defense is a good offense and will take any opportunity to demonstrate superiority, strength and power. Other aggressive behaviour shows up as passive-aggressive, that is, they become obstructionists by offering resistance that shows up as helplessness, procrastination, hurt feelings, even after multiple requests to stop.

Deception

Truth twisting, half-truths, withholding some information, lies, bad-mouthing, gossip, blaming, negativity, clique forming with the intent to exclude or discriminate against another, are all forms of deception. These have the effect of creating feelings of insecurity, uncertainty and lack of confidence in others.

Manipulation

The most recognizable manipulation game is whining or complaining which focuses attention on how others are wrong, guilty or incompetent. They seek to get their own way by maneuvering others into the bad guy role, or the rescuer. The manipulator does not trust their world to respond in predictable and reasonable ways, and so they try to trick their world into responding opportunistically to their advantage. An example is low-balling one’s estimates.

Protection

Active protectors will hide behind paperwork, legal agreements, non-disclosures, red tape and anything else that will protect them in the event of a collapse or blame from above. In being overly protective they cause others to distrust them. Passive protectors take no risks, remain silent, withdraw, pass the buck, make no commitments, and hide behind obscure rules, convoluted processes and abstract reasoning. Gatekeeper protectors keep people away from the boss, for example.

Detraction

This goes hand-in-hand with judgment and negativity. The person is typically judgmental, overtly critical, overly analytical, or highly skeptical. They find something wrong, play holier-than-thou and seize opportunities to appear wiser, stronger, more experienced, to your detriment. Some are cynics who cannot look at the world from a positive point of view and they are the ones that can suck life and hope from an organization.

Transaction – Neutral

At this point there is neither trust nor distrust.

Above the Belt Behaviors

Relationship

Building trust starts with building a relationship through connected listening that validates the other’s perspective. Listening with empathy, an open mind and an open heart will create respect. When both parties feel respected, both can be counted on to understand personal interests, needs and concerns of the other, which gives the assurance that both will be better off from having met.

Guardianship

This level of trust provides safety and security. It can be one-way, for example as a parent to child, or it can be mutual guardianship as in soldiers on a battlefield. Every employer has a duty and responsibility both morally and legally to protect their employees’ safety on the job, to provide a fair wage, provide a work environment free from harassment. Employees have a duty and responsibility to maintain guardianship over the workplace by not stealing, by reporting hazards, contributing ideas to improve competitive advantage and ensure the well-being of their teammates. At the guardianship level the issue of honor and integrity are critical to building trust.

Companionship

Being a companion means trusting enough to work productively in teams. Team members know breakdowns will not be destructive, we can share our thoughts, workspace, and concerns without fear of retribution, disrespect or dishonor. The team contributes to each other’s wellbeing. Decisions are made by considering what is best not for the individual, but for the greater good of the company, team and future of the business. There is a common vision and aligned interests.

Fellowship

This level of trust also includes a sense of belonging and commitment. Because of the weakening bonds of the modern family structure, for many the workplace becomes a surrogate family and the workplace carries with it a desire for fellowship.

Friendship

The power of friendship lies not just in the bond of familiarity, but also in the mutual commitment to each other’s well-being. It includes the prior levels of trust and adds energizing and vitality-creating forces including compassion, non-judgmental presence, protection, loyalty, and playfulness.

Partnership

A partnership is designed to respect and cherish the differences in thinking and capabilities between two or more people or organizations. It is the combination of differing strengths and the alignment of common purpose that makes a partnership effective. For example, a restaurant partnership might have two partners, one of whom excels at the creative kitchen tasks while the other excels at organizational tasks such as bookkeeping and staffing. A partnership has shared vision, shared planning and shared resources, risks and rewards.

Creationship

A “creationship” implies the ability to do something extraordinary – co-creation together. A creationship embraces prior elements of trust building, and then, secure in the absence of fear, unleashes a connection between the hearts and minds of the co-creators. Collaboration between musical composer teams to bring about famous Broadway musicals is one example. Scientific teams that brought man to the moon is another.

Model

While there are multiple models in existence consulted for resolving conflict, we have chosen to provide you with a four-stage model. In more advanced classes, you might see more fleshed out versions of the model tailored specifically to the skills you will be learning in those courses. However, in a constructive discussion designed to resolve conflict, in whatever situation it may appear, the following four-part process can be consulted:

| 1. Set the stage. How to talk ? | |

| Set a collaborative tone by working together. obtain agreement from the other person to enter into a discussionarrange a convenient time and place, where you may talk without interruptionwelcome the other person and express your commitment to resolve the problemdetermine the guidelines for the discussion, such as who needs to be involved or informed; who can make decisions; what ground rules will be in place to manage emotions, such as respectful language and no interruptions | |

| 2. Form the agenda. What to resolve? | |

| Identify the issues of concern. agree on what needs to be resolved (issues)use neutral wording so that each person is comfortable discussing the topics if there is more than one issue, by picking the topic you both wish to start with | |

| 3. Seek understanding. Why is that important? | |

| Discover underlying interests and move toward a mutual goal. use active listening skills to gain understanding of the other person’s perspective and learn what is important about that (interests)express your own perspective and interests, using assertive language, in order to be understoodtake care to employ skills and techniques to manage the emotional climate summarize each person’s interests | |

| 4. Find a resolution. How to resolve? | |

| Brainstorm creative, mutually beneficial solutions. generate options choose a solution that meets the needs of both individualsplan the implementation of the resolution (action plan)set a date for following up to ensure the plan is working and be prepared to make whatever adjustments are necessary to make it work |

Positions, Issues, Interests

Definitions

| Position | A solution that meets a person’s own needs, often expressed as demands or conditions beginning with these terms: I want… I don’t want… You better…or else… We have to… You will… You have to… I will not…. It needs to be… Often presented as a one-sided solution. |

| Issue | The topic/problem/dilemma about which parties disagree and which forms the basis for the dispute. What needs to be discussed/resolved? Issues can be identified by listening to the position(s) of the party/parties. |

| Interests | A collection of needs and motivators, which a person must have met by any resolution or agreement. Interests are any expression of priorities, expectations, assumptions, concerns, hopes, beliefs, fears, values, or needs. |

From these definitions, we are able to realize how much interests influence our thoughts, feelings, and behaviour in everyday life. In any given situation, one or several of our interests, sometimes without conscious awareness, might motivate us. This motivation is what determines our opinions and our approaches. We can also see that, unlike positions or issues, interests allow us to get to the root of a concern and seek better understanding.

Given the vast number of interests we may have, in addition to the great variation in personal experience, cultures, life styles, and access to resources, it is little wonder that we may encounter circumstances in which our interests are or appear to be incompatible with those of other people.

If we find ourselves in a conflict, our interests determine the position we take and how we see a particular matter being settled or resolved. We may have very strong emotions tied to certain interests that serve to strengthen our attachment to a particular situation.

It is important in alternative dispute resolution, especially when moving forward into mediation and negotiation, to focus on uncovering interests instead of someone’s position or solution. By being interest-based we are more likely to find out what the heart of a problem is and what needs to be solved instead of just applying a band-aid solution.

Identifying Issues

When individuals are in conflict they are most likely to first put forward their positions. Their positions are the solutions they prefer and how they envision the conflict being resolved to meet their personal needs. Each position is, therefore, a one-sided solution and often in opposition to that of the other party, thus giving rise to the conflict. A person’s attachment to his or her position is driven by that person’s underlying interests and hence is often accompanied by a marked degree of emotion.

The purpose of Phase 2 of the Model is to extract from the positions the subject matter or problem areas or topics (issues) to be resolved. Once identified, subjects or topics are listed to form the agenda that provides the roadmap and focus for the dispute resolution process.

In order for the issues to be acceptable to both parties, they must be identified in language that is neutral and not seen to favour one party over the other. They must not suggest any particular outcome. Consider the following example:

sale of the company (presupposes a sale which one party may oppose and which limits the options for resolution)

future of the company (neutral, not favouring either party, and unlimited in terms of possible solutions)

Adjectives often relate to specific types of solutions and suggest premature evaluation and, therefore, are not useful in stating issues

respectful communication (may indicate one party’s preference and may be interpreted as implying that this is not currently happening, thereby having the potential to lay blame)

a communication plan (neutral, and leaves the opportunity for parties to discuss and determine a mutually acceptable resolution)

The other critical characteristic of an issue is that it be something which is negotiable such as actions, behaviours, and use of resources. Core values and beliefs, while very meaningful and deep-rooted, often cannot be negotiated. As interests, however, they need to be recognized and understood by both parties.

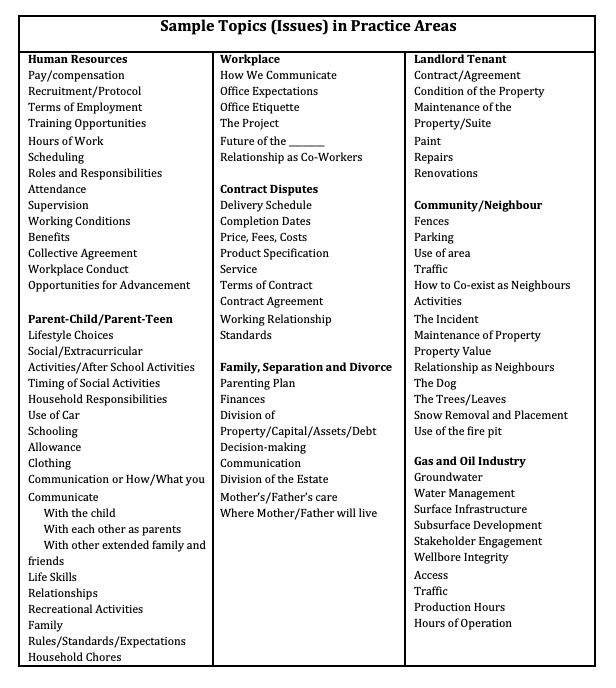

Below are examples of neutrally worded issues that may be helpful to have in mind, depending of course on the subject of the negotiation. As a negotiator your job is to wordsmith the topics so you and the person(s) you are negotiating with are comfortable with the agenda topics. There is more than one way to define the issue. Before writing topics up on flip chart, ask yourself: Is this resolvable? Is this neutral for both of us and will it give focus for what we need to discuss and resolve?

Theory: Types of Interests

When we are entering into a negotiation with someone, it is important to be cognizant of what external factors may be affecting ourselves and the other individual(s).

Game Theory

In its simplest form, Game Theory suggests that people tend to begin interaction in a competitive mode, expecting a zero-sum interaction. That means that each will try to get the most out of any situation even at the cost of the other. Game theory shows why two purely “rational” individuals might not cooperate, even if it appears that it is in their best interests to do so.

If that is true it’s all the more important for us to listen, probe, and reframe, in order to explore interests. Our exploration of interests helps the person move into a collaborative mindset.

Human Needs Theory

Human Needs Theory suggests that humans are striving for two basic things: happiness and betterment. All decisions are made based on love or fear. Happiness depends on getting needs and values met.

Burton and Fisher define the most powerful interests as human needs, which are identified as security, economic wellbeing, a sense of belonging, recognition, and a sense of control over one’s life.

People experience conflict when there is a difference or perceived difference in needs, values, beliefs, priorities, values, or attitudes. Differing positions are a result of those differences and can result in a dispute.

Opposing or differing positions or viewpoints can pose a threat, often resulting in fear and tension. Determining underlying interests, both common and unique, allows the opportunity for participants to think of and consider other possible options.

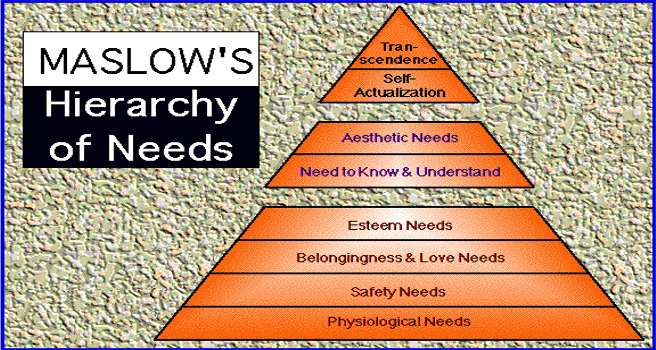

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs

Maslow described basic human needs as forming a hierarchy based on two groupings: deficiency needs (psychological, safety, belongingness, esteem) and growth needs (understanding, aesthetics, self-actualization, transcendence).

His theory suggested that within the deficiency needs, each lower need must be met before moving to the next level. The deficiency needs must be met before the growth needs will be sought after.

In everyday life we sometimes see this happening when someone is experiencing a very difficult time financially, and, through necessity, their focus is on accessing basic resources such as food and shelter for themselves and their family. They are simply not able to give priority to additional educational opportunities (increased understanding or recognition) for themselves and nor can they be as concerned about reaching out to help others achieve their potential (transcendence).

Interests

Interests begin to develop in early childhood based on background and life experience. Interests often mean different things to different people. The intensity with which interests are held varies, and the impact they have on an individual varies as well. Interests such as beliefs, fears, values and needs (BFVNs) are likely to remain constant throughout life whereas concerns and priorities may change with circumstances. What is common to everyone is the existence of interests at some level, and the need to explore these to understand another person. If it is determined that two individuals share an interest and are motivated equally by it, this can provide a building block for resolving dispute between them.

PEACH BFVNS

PEACH is an acronym representing the starter questions used to uncover the interests that are important and often serve as motivators for individuals to adopt particular perspectives or positions in conflict situations.

These motivators include: Priorities, Expectations, Assumptions, Concerns, and Hopes.

Some other interest-based questions include: Beliefs, Fears, Values, and Needs (BFVNs).

Sometimes, individuals may not be aware of what matters most to them or is underlying their positions in a given situation. Also, it is important to be aware that interests may have different meanings for different people, and that they may also have a deeper meaning than first appears, creating the need for probing and clarification.

Common Interests

There are many interests that are frequently identified as being important, such as the ones listed in the following table. When these needs are common to both parties in a conflict, they create a basis on which to build understanding and create mutually satisfying resolutions.

However, we must be very careful not to be lulled into thinking that a particular interest holds the same meaning for us and the other party. Many things affect what we value and why, and how we prioritize interests at any given time and situation. Do not assume; always ask to clarify!

List of Common Interests

| Acceptance | Accountability | Achievement | Acknowledgement |

| Adventure | Affection | Appreciation | Authority |

| Autonomy | Belonging | Beauty | Being Heard |

| Celebration | Clarity | Commitment | Communication |

| Competency | Connection | Contribution | Control |

| Creativity | Efficiency | Empathy | Equality |

| Excitement | Experience | Expertise | Fairness |

| Financial Security | Freedom | Fulfillment | Fun |

| Health | Honesty | Inclusion | Imagination |

| Independence | Input | Integration | Intimacy |

| Knowledge | Learning | Listening | Love |

| Motivation | Nurturance | Opportunity | Organization |

| Originality | Peace of Mind | Privacy | Profitability |

| Recognition | Relaxation | Respect | Responsibility |

| Safety | Satisfaction | Security | Self Assured |

| Sense of Order | Sensitivity | Sharing | Standards |

| Strength | Support | Teamwork | Time |

| Trust | Understanding | Unity | Validation |

References:

Helmstetter, S. (1982). What to Say When you Talk to Yourself. New York, NY: Simon and Shuster Inc.

Lynch, R. P. Architecture of Trust. Retrieved: July 19, 2012 at: http://www.warrenco.com/articles.html

Senge, P. M., Kleiner, A., Roberts, C., Ross, R. B., & Smith, B. J. (1994). The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook. New York, NY: Currency/Doubleday.

The below the belt model was generously shared by Robert Porter Lynch at an Alberta Arbitration & Mediation Society (AAMS) conference during which he presented material on the architecture of trust.

Huitt, W. (2007). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved from: http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/conation/maslow.html[TB10]

© 2014 ADR Institute of Alberta

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, or any information storage and retrieval system. Permission is not given for preproduction of the materials for use in other published works in any form without express written permission from the ADR Institute of Alberta (“ADRIA”), with the exception of reprints in the context of reviews.