Dealing with Difficult Behaviours

When encountering difficult behaviours it can be hard to communicate properly, make you feel like you will never get to a solution, drain your energy, and leave a feeling of hopelessness. While you can’t change people, you can change the way you communicate with them, which might even lead to them changing their own behaviour.

Applying the Skills and Model

Remember, before you undertake a role-play, give some thought to the following suggestions of how to handle someone who resists the process. Consider the following ways to invite or require the other party to move from positions to interests.

Concentrate on the merits, rather than the positions. In effect, you can change the game simply by starting to play a new one. Focus on objective criteria.

Recognize strategies. Typically the other person’s resistance will consist of three manoeuvres: asserting their position forcefully, attacking your ideas, and attacking you. In response:

- Don’t attack his or her position, look beneath it. Seek out and discuss the issues/interests underlying the other side’s position.

- Don’t defend your ideas. Invite criticism and advice. Instead of asking him or her to accept or reject an idea, ask what the effect might be. Examine his or her negative judgements to determine underlying needs and to improve your ideas, from the other person’s point of view. Ask what he or she would do in your position.

- Redirect an attack on you as an attack on the problem. Listen to the other person and show you understand what is being said. When the individual is finished, recast his or her attack on you as an attack on the problem.

Ask questions and pause. Ask about the other person’s interests rather than his or her position. Questions are effective as they allow the other person to get his or her points across so you can understand them. Questions often encourage the other person to confront the problem, and strive to educate rather than criticize. They provide no target to strike at and no position to attack.

Use silence. If the other person has made an unreasonable proposal or an attack you regard as unjustified, the best thing to do may be to sit there and not respond. Resist the urge to engage in a debate or defend yourself as either of these reactions will put you into a positional bargaining mode.

Maintain open lines of communication. Use statements such as “Let’s make sure I understand what you said” or “Let’s take a moment to go over this again“. If they resist, you can terminate the process and arrange for a third party (arbitrator/mediator) to assist or choose your BATNA.

Dealing with Difficult Behaviours

Definitions

| Anger | the physiological, emotional, and psychological response to an event (internal or external), which is perceived to be threatening, frightening, hurtful, embarrassing, frustrating, or irritating. Synonyms: resentment, frustration, irritation, annoyance, rage, fury, outrage. |

| Threat | an indication of a negative event that is perceived as leading to the risk of some kind of loss. |

| Resistance | the force applied in response to something perceived as destructive, threatening, or not in one’s interest. |

Types of Difficult Behaviour

There are many common types of difficult behaviour that people exhibit. As Jon Bloch notes in Handling Difficult People, there are ten difficult behaviours that are commonly found, including: bullying, mouthiness, becoming a brick wall, complaining, being overly dramatic, being a know-it-all, procrastination, snobbery, temper tantrums, and two-faced behaviours.

Bullying

This behaviour is exactly as the name calls to mind: a giant bully. This may take the form of threatening, name-calling, put downs, and placing other people in embarrassing situations. Bloch says that this sort of behaviour often takes place in people who enjoy power, and employ power-getting tactics by putting down others in an attempt to make themselves look good.

Mouthiness

Mouthiness is a trait best classified by being unable to stop talking all the time. It is often accompanied by a lack of a filter, meaning that whatever is thought comes out of the mouth, with little to no regard to privacy or setting. Bloch calls this behaviour type the Big Mouth, and says that people who often fall into these behaviour patterns are actually usually quite socially anxious and downright shy, and that in an attempt to fix this behaviour, often feel a need to fill the silence— every time one might arise.

Brick Wall

Brick walling is an extreme form of stubbornness where a person might refuse to budge at all on a point, sometimes to the point of refusing to talk at all. This type of behaviour might only surface when certain issues are brought to light, such as politics or religion, but can also arise at the slightest sign of content for those who are defensive and dislike handling conflict.

Complaining

Not your regular run-of-the-mill complaining that might occur when someone has had a particularly stressful day, but instead complaining that seems to take place no matter what. This kind of behaviour is extreme, and the person exhibiting will often find nothing positive at all to say about anything. This kind of behaviour can be very draining for both people exhibiting and enduring it.

Overly Dramatic

The person exhibiting this behaviour is also referred to as melodramatic. This type of behaviour often manifests in two ways: the world is always ending and someone else needs to fix it. Sometimes even the simplest problems can be wound up into total disasters, and exaggeration might turn into lying in a bid for attention.

Know-it-all

This type of behaviour often makes itself well-known right away. It is not enough just to know a lot about many things, or even to know everything about one thing, this behaviour manifests into never being wrong about anything ever, even at the cost of making something up just to save face.

Procrastination

Chronic procrastinators never seem to finish everything and always have a multitude of projects that are in various stages of completion. Bloch notes that people who are perfectionists, and who become so overwhelmed by wanting everything to be perfect that they put off starting the projects and never seem to complete anything by a deadline, because they fear that the results in their head might not match the actual reality, often exhibit this kind of behaviour.

Snobbery

Bloch reminds us that while everyone has a tendency to behave snobbishly once in a while, that the type of snobs addressed here are the kind who are never satisfied by anyone or anything ever, and that their standoffish behaviour can make it hard for anyone to get through to them.

Temper Tantrums

Temper tantrums can manifest naturally when people are very young children, or are occasionally experiencing the kind of turmoil that leads to a physical manifestation of an emotional break. Where this behaviour becomes quite difficult to handle is when a person should have outgrown the tendency to cry and scream when they do not get their way, and when they resort to this tactic quite regularly, making them volatile and unpredictable. This behaviour can also turn quite manipulative, including having people threaten serious harm to themselves or others if they feel that they are not getting their way.

Two-Faced

This behaviour can be quite damaging to everyone exposed to it, as the tendency is to outwardly appeal to everyone about everything, and then to gossip and cause turmoil amongst others from what is learned in confidence. Often, this behaviour occurs when people are looking explicitly to create drama and to look like a true friend to as many people as possible.

Dealing with Problematic Behaviour

While dealing with all difficult behaviours, try to empathize. Understand that everyone reacts differently to situations, and that what might be unacceptable to you might be perfectly fine with someone else. Try to understand what is motivating the behaviour of the person and what their intentions may be. Also work to recognize that you might be behaving difficultly too, and that you might be contributing to their behaviour.

On your side of the table, know your needs and your options, in case the difficult person is not cooperating and you need to regroup.

Four Approaches

1. Stay and do nothing. Complain to people who can do nothing. This lowers morale and productivity and postpones effective action.

2. Vote with your feet. Not all situations are resolvable and not all situations are worth resolving. Sometimes it is worth it to walk away.

3. Change your attitude. You can learn to see the person differently, listen to him or her differently, and feel differently about him or her. You can make attitude changes that set you free from your reactions to problem people.

4. Change your behaviour. If you change the way you deal with difficult people, they have to learn different ways to deal with you.

At the end of the day the choice is up to you.

Anger

Anger and Threat

Anger is one of the first emotions human beings experience and probably one of the last emotions we learn to manage effectively. By four months of age, the muscles involved in the display of anger have developed. For many of us, a lifetime is spent in denying, suppressing, displacing, or avoiding this troublesome emotion. Is it any wonder that dealing with anger is so difficult?

Anger happens when we perceive an event as threatening or when we experience the frustration of unmet needs. As a perception is formed, assumptions are made about the possible danger of that threat. The assumption is then checked against our perceived ability to deal with that threat. If we conclude that the threat is not very great, or that we are powerful enough to confront it successfully, a calm, unflustered response can occur. If we decide that the threat is dangerous or that we are powerless to handle it, anger may emerge in an effort to reduce the threat and to protect ourselves.

Anger may also be triggered when our needs or desires go unanswered. Demands, requests, and expectations which do not receive a satisfactory response might result in an irritated or angry reaction. This is particularly common in our culture when we feel we have clearly communicated our expectations to those in a position to respond, and yet they do not react accordingly. We may interpret their lack of response as threatening, challenging, unjust, unwarranted, or simply ill-mannered. It is this interpretation which often triggers the angry response and it is exasperated by our workplace hierarchy. How many times have you heard a manager or supervisor with this complaint: “he just doesn’t listen; I tell him how to do the work, when I expect, and why it needs to be done, and still he doesn’t get it right. He is either stupid or doing this purposely to get to me.”

An Ecological View

The feeling of anger is almost always valid. It is merely a signal from your body that something is wrong, that a problem exists. The problem or conflict may have arisen between you and the outside world, or internally, related to your needs and beliefs. It may be a real conflict or an imagined one. Nevertheless, the feeling of anger is a real message that you perceive a problem or conflict. Resist judging the feeling of anger in yourself or others. Instead, look or listen for the source of the problem or conflict and try to resolve it.

Angry behaviour, on the other hand, might or might not be a direct expression of angry feelings. In our society, angry behaviour has many other payoffs besides expression. Because of this, it is useful to assess angry behaviour in ourselves and others to determine the meaning of the behaviour in context. Angry behaviour may be any one of the following:

- an appropriate expression of feeling

- a displaced expression of feeling

- a confused expression of feeling

- an instrumental behaviour, which has the goal of intimidating or confusing the target person

- a ritual or tantrum behaviour, which has a goal of . . .

- getting attention

- gaining control

- communicating helplessness

- seeking revenge

Emotional Triggers

The word “trigger” can mean many things. An event can trigger a sequence of events (e.g., the no-confidence vote triggered an election). A trigger can be the firing mechanism of a weapon. And for many helping professionals, “trigger” is reserved for trauma activation – e.g., certain settings, images, sounds, smells, flashing lights, etc., may trigger/activate intense feelings of fear and threat in a veteran/first responder, or a survivor of war, genocide, sexual violence, etc. such that that person may reexperience the traumatic event again as though it were currently happening all over. Of course, this is but one symptom of trauma.

Trigger has also been added to our lexicon as shorthand for “made me feel bad/sad/mad”. Consider that when someone says, “when he emptied the milk and put it back in the fridge, I was triggered”, it is unlikely that they have been traumatically activated. Instead it is more probable that they feel annoyed, or even very angry.

Emotional triggers can be words, people, opinions, situations, or environmental situations that provoke an intense and sometimes excessive emotional reaction within us. Often these reactions involve negative feelings such as anger, frustration, shame, disgust, or fear. They are often based in memory, but not necessarily. These situations are deeply connected to our unmet needs and stem from the need or desire to preserve the integrity of the self/ego.

An emotional trigger is:

An event/situation + a fear/threat/unmet need = a sequence of events within our brain that results in an emotional reaction

Example:

| Event | “While biking and following the rules of the road, I was hit by a car that should have seen me. |

| Fear/Threat/Unmet Need | I was really scared, I could have been seriously injured or worse. |

| Emotional Reaction | When the driver got out to apologize and check that I was alive, I was shaken and very angry. I would not let her feel ok. My fear led to anger which led to yelling, cursing, obscene hand gestures, and (probably) name calling. Recognizing that I was afraid when I was hit by the car explains but does not excuse how I reacted. At the time I wanted her to feel so bad that she would never want to drive a car again and I wanted to feel in control.” |

| Event | “In high school I did something very stupid and disrespectful. I knew it was wrong immediately. I told my classmate that I would tell the teacher myself, but he told her first. |

| Fear/Threat/Unmet Need | I wanted to be viewed as someone with integrity, as respectful, responsible, and trustworthy. Despite my lapse in judgement, I believed myself to be an accountable individual willing to own up to mistakes. |

| Emotional Reaction | I was angry with my classmate who told the teacher before I had the chance. My ego was bruised, and I was embarrassed by my action. I also felt that the teacher could no longer trust me. I blamed the classmate for my loss of face and yelled at him, calling him a “rat” in front of his friends” |

It’s easier to forgive misbehavior in ourselves and others once we understand this powerful connection between threats/unmet needs, emotions and reaction. Emotional triggers explain, they don’t excuse. Recognizing our triggers makes us responsible for recognizing our trigger situations so we can change our unconscious reactions.

How to Identify Emotional Triggers

- Pay attention to your body and what’s happening

- Notice what thoughts fire through your head

- Who or what triggered the emotion?

- What happened before you were triggered? (Sometimes it’s what happened just before or the context)

- What needs of yours were not being met?

You may need to engage in self-talk first to be able to relax and recognize you are reacting to a trigger before you can analyze the situation. Remember, naming your emotions can have a powerful effect on your ability to control them. Once you are in control, you can change your emotional state and decide how to respond.

Theory: Anger Arousal Cycle

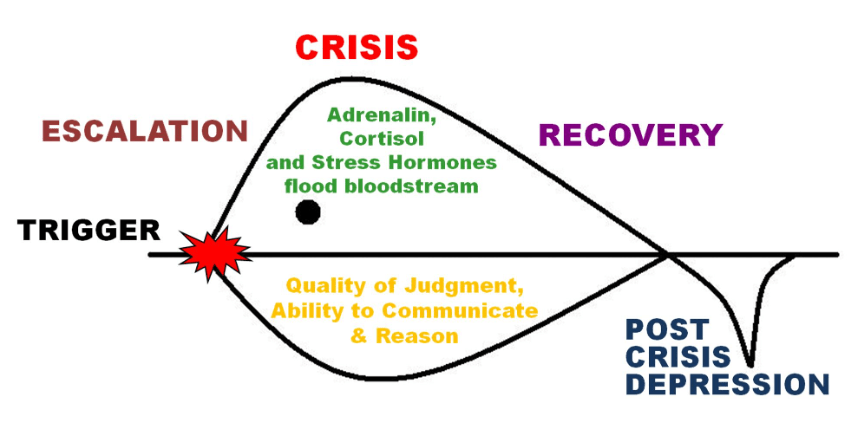

There are five stages to the arousal cycle when you are in a conflict situation. These are shown on the illustration below.

The Trigger Phase

There is usually an event that triggers the arousal cycle: you get into an argument or you receive some information that upsets you. You see yourself as threatened (emotionally, mentally, or physically) at some level and your physiological systems begin preparing to meet it. For example, someone walks up to your workplace front counter or desk, starts banging it, and yells that someone better start talking to him or else! In this situation, the trigger is external. Triggers can also be created internally through memory, perception, or one’s own stress level.

The Escalation Phase

During the escalation phase, the body’s arousal systems prepare for a crisis. The body prepares to attack or defend itself by pumping adrenalin into the blood stream, which results in the following physical changes:

- Respiration rate increases and rapid breathing occurs.

- Heart rate and blood pressure elevate.

- Muscles tense for action: jaw, neck, shoulders and hands become taut.

- Voice pitch alters and the volume gets louder.

- Eyes change shape: pupils enlarge, brow falls, gaze becomes steely.

The Crisis Phase

This phase begins with the “fight or flight” response. The body has maximized its preparation and a physiological command is issued: Take Action! Unfortunately, our quality of judgment has been significantly reduced at this point and decisions are not made with our best reasoning ability. People in the crisis phase are highly volatile and need to be addressed in a simple, direct and non-provoking manner.

The Recovery Phase

Once some action has been taken to resolve the crisis phase, the body begins to recover from the extreme stress and expenditure of energy. Unfortunately the adrenalin does not leave the blood stream all at once so the level of arousal tapers off gradually until normal limits are reached. Quality of judgment returns as reasoning begins to replace the survival response.

The Post-Crisis Depression Phase

After the normal physiological limits have been reached, the body enters a short period in which the heart rate slips below normal levels so the body can regain its balance. During this phase, awareness and energy return to the forebrain to allow the person to assess what just occurred. This assessment often leads to feelings of guilt, regret, and emotional depression.

In the last section, the focus was on escalation of emotions, so let’s start here with some of the most important information you need to know about managing emotions. Predictably, these notes begin with how to manage your own emotions and then will progress to how to help others manage their emotions.

Defusing Strategies: For Yourself and For Others

The best way to manage our own emotions is with self-talk. Self-talk is the phrase we use to describe that voice in our head that constantly tells us what to think and how to feel. In a way, it’s the narrator of our own life movie.

1. Remain calm yourself.

Use productive self-talk.

Ensure physical safety.

2. Nonverbally reassure the other person.

Allow adequate personal space.

Use a supportive stance.

3. Encourage talking.

Use attending body language.

Don’t interrupt.

Use minimal encouragers.

4. Show understanding.

Acknowledge feelings

Match and lower intensity.

Respond empathically.

Ask open-ended questions.

Clarify by paraphrasing and summarizing.

Reframe statements.

Invite problem solving.

Use the individual’s name.

Be prepared to repeat yourself

5. Commit to resolving the issue.

Emphasize willingness to resolve the issue.

Acknowledge the importance of resolving the issue.

6. Help the other person save face.

Reassure them.

Offer the option to pursue the issue later.

Refrain from openly judging their behaviour.

Self-talk

When we are exposed to a threat, our self-talk tends to become unproductive and often very loud.

The only way to change how you are feeling and reduce the emotional escalation is by paying attention to your negative or unproductive self-talk. You can do this by confronting it by converting it into constructive self-talk. As soon as your thinking changes, your feelings and behaviours will follow.

How you interpret any event will impact how you feel about it. All feelings are a reflection of your self- talk. If you are feeling nervous about an upcoming meeting, then listen to what you are telling yourself about the meeting and you will understand your feelings much better.

Once you have identified the unproductive self-talk you are using, you can learn how to change it.

Here are some steps to follow:

| Step | Action | Recommended thoughts and corresponding actions |

| 1. | Identify impulse | “I am thinking …” |

| 2. | Identify feelings | “I am feeling . . .” |

| 3. | Recognize cues | “I need to stop and and think calmly.” |

| 4. | Respond physically | “I must breathe slowly, relax my jaw, relax my muscles, plant my feet firmly on the ground.” |

| 5. | Reassure myself | “This is a problem. I can handle it. I have the skills I need. I know what to do.” |

| 6. | Shift my approach | “I must become curious, instead of being defensive or judging.” “He is not yelling at me – he’s yelling to be heard.” “She is really upset – I wonder what the problem is?” |

| 7. | Be prepared to listen and reflect | “I need to listen and let him or her know what I heard.” |

If we do not manage ourselves through the use of productive self-talk, we drastically reduce our ability to effectively deal with another’s hostility.

Conversely, if we can take time and make an effort to understand what is happening internally for us, we have an opportunity to engage ourselves in a process of becoming calmer and regaining control, both physically and emotionally. We are then able to manage our response more effectively, without defending or judging, and thereby assist the other person to also become calmer.

Setting Limits

Setting limits is a new skill to add to your portfolio. Sometimes in an emotionally charged situation it becomes necessary to establish some limits if the discussion is to continue. Otherwise, the conversation will be unproductive: emotions will prevail or escalate, understanding will not occur, and the goals will remain unmet. The responsibility to set limits will be yours, as the skilled participant; use the DESC model you have already learned (underlined) with three additions: acknowledgement, commitment, stating preference.

- Acknowledge “I can see you are angry.” (your observation might be “loud voice”, or “red face”)

- Commit involvement, “We do need to solve this.”

- Describe trigger “When I get called . . .” or “When I am told . . .” (“names” in the first example, or ”it’s not my business” in the second example) “.

- Effect. . I get . . .” or “ . . . I feel . . . ‘ (feelings like “upset” or “really frustrated”)

- Specify “I want . . .” or “I need . . .” ( “to feel respected”)

- State preference “It would be better for me if we . . .” (“use respectful language”)

- Consequence “That way we can . . .” (name the benefit “both listen to understand”)

Disengagement

Occasionally, it is not possible to sufficiently defuse the emotions of another person in a particular situation in order to proceed with a productive discussion. Therefore, attempting to continue could cause considerably more harm to the relationship and significantly increase the level of conflict. Given those circumstances, it becomes necessary to halt the process.

Sometimes you may find yourself triggered by what the other person is saying or doing, and discover you are unable to control your emotions well enough to keep managing the process in a positive way. It then becomes necessary for you to remove yourself to regain control of your feelings.

There may also be a time when, because of a high level of emotion and a potentially volatile situation, it is difficult to ensure the physical safety of the individuals present.

In any of these situations, disengagement is the appropriate action to be taken. Certainly in the case of a physical threat, disengagement must happen immediately. In some circumstances it may be possible to resume a discussion at a later date.

To accomplish disengagement, use the following five steps:

- Acknowledge “I can see you are angry.” (your observation might be “loud voice”, or “red face”)

- Commit involvement, “We do need to solve this.”

- Describe “I am hearing a lot of yelling.”

- Effect “which is making it difficult for me to listen.”

- State “I’m too upset right now . . . I really need a time out.” If appropriate, state intention to return “I will be back in half an hour.” or “Let’s resume in half an hour.”

- Consequence “That way we can work towards a solution.”

- Leave. Leaving is the most important step in disengagement.

Overcoming Resistance

Being able to manage difficult or emotional situations begins with recognizing there could be a possible push back response. In these situations, reflective listening and assertive speaking are useful skills as described in the following table.

| If you experience | then … |

| Hostility | reflect content and feeling with particular emphasis on reflecting feeling avoid getting side-tracked or hooked into the attack treat the party with respect re-assert |

| Questions | reflect content rather than answering the questions provide data if needed for clarification be silent |

| Debate | refuse to engage in the debate use reflective listening skills |

| Tears | provide tissue reflect feelings re-assert adjourn and reschedule if necessary |

| Withdrawal | wait for responses acknowledge the reaction re-commit |

Listen carefully for any statements acknowledging validity or possible solutions. If these occur, reflect them back and then offer silence.

References:

Bloch, J. (2013). Handling difficult people. Avon, MA: F + W Media Inc.

© 2014 ADR Institute of Alberta

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, or any information storage and retrieval system. Permission is not given for preproduction of the materials for use in other published works in any form without express written permission from the ADR Institute of Alberta (“ADRIA”), with the exception of reprints in the context of reviews.